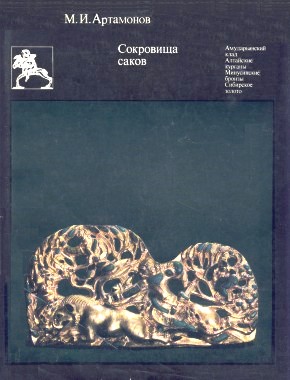

Ì.È. Àðòàìîíîâ Ì.È. Àðòàìîíîâ

Ñîêðîâèùà ñàêîâ.

Àìó-Äàðüèíñêèé êëàä. Àëòàéñêèå êóðãàíû.

Ìèíóñèíñêèå áðîíçû. Ñèáèðñêîå çîëîòî.

// Ì.: «Èñêóññòâî». 1973. 280 ñ. (Ñåðèÿ: Ïàìÿòíèêè äðåâíåãî èñêóññòâà.)

Summary.

I. The Iranian Speaking Population of Soviet Central Asia and South Siberia in the 1st Millennium B.C. ^

In the 1st millennium B.C. Iranian-speaking peoples inhabited all of Soviet Central Asia and a large part of South Siberia. Their culture, known as Andronovo culture, spread over that vast area. It reached the Minusinsk lowland in the east, merging in the west with the kindred timbered-grave culture of the south of Eastern Europe; its southern border in Central Asia was the Kopet-Dagh, and in the north it was bounded by the taiga forest belt.

According to Greek and Persian sources, the nomadic and semi-nomadic population of Soviet Central Asia went under the name of Saka. The Persians distinguished Haumavarka Saka (probably identical with the Amyrgeian Saka of Herodotus) who lived in the south of the territory; Saka Tigrakhauda — «beyond Sogd», in the east of Soviet Central Asia; and Saka Taradaraya (living «beyond the sea or river») in the steppes stretching north-east of the Jaxartes (Syr Darya River). The north-western part of Central Asia along the Aral Sea was Inhabited by tribes which Herodotus called Massagetae; their neighbours further north-west, around the Southern Urals, were the Issedonae. Chinese sources mention the Saka as the Yüeh-chih of North-Western China and Western Mongolia.

The Persian conquest of Central Asia began under Cyrus II, but it was only in the reign of Darius I (in 519 B.C.) that part of the Taradaraya tribes were finally subjugated. When Alexander the Great destroyed the Persian Empire, Persian possessions in Central Asia were taken over by the Greeks. Later the southern lands became part of the Graeco-Bactrian Kingdom which formed around 250 B.C. The Yüeh-chih, pressed by the Huns, migrated westward. In 128 B.C. they conquered the Graeco-Bactrian Kingdom to set up several Independent lands on its territory, which ultimately were Joined to the Kushan Empire. In the south-west of Central Asia the Parthian Kingdom arose in the 3rd century B.C., and it brought under its sway Iran and Mesopotamia.

II. Works of Saka Art from Soviet Central Asia and West Siberia. ^

So far but a few archeological relics of the Saka have come to light on the territory of Soviet Central Asia. Of paramount importance among these is the treasure of the Oxus — a hoard of gold objects discovered by chance in Tajikistan, on the right bank of the Amu Darya (Oxus) near the Afghan border. This was most probably a temple treasure buried in the ground at the approach of Alexander’s forces in 329 B.C. It comprises votive plaques depicting Persians, Saka and also animal figures; sculptured figurines and heads; armlets, rings and other temple offerings which represent Iranian art in the 6th-4th centuries B.C.

Of special interest are the objects with coloured inlay, e.g. the armlet terminating in gryphons, the aigrette and other objects where stylized, geometricised forms of inlay are used in place of relief.

The present review of Saka works of art opens with an analysis of finds from the upper reaches of the Amu Darya in the Pamirs. From one of the burial mounds came bronze plaques in the shape of a bear and the protome of a bear (6th century B.C.); from another mound, dated later (5th or 4th century), came a sword hilt with a goat figure and goats’ heads. Jewellery with turquoise inlay from the Tulkhar burial ground, southwestern Tajikistan, is dated in the end of the 1st millennium B.C.

(269/270)

Two burial grounds, Tagisken and Uigorak, were excavated in the Aral Sea area, in the old delta of the Syr Darya. Found in the former (earlier) burial were parts of a gold sword casing with the head of a mountain ram and two recumbent wolf figures. Among the finds were a gold plaque in the shape of a recumbent goat, gold plaques in the shape of walking and recumbent lions and bronze buckles made up of pairs of horses’ heads. A similar buckle from the Uigorak burial site is shaped as a deer in side-view. Other annular buckles from Uigorak are decorated with ornamental designs and have projections in the shape of a stylized ram’s head or a scroll. The animal-style objects from Tagisken were made not earlier than the 6th century B.C.; those from Uigorak can be dated in the 5th-4th centuries B.C.

A boulder-and-earth burial mound in Central Kazakhstan yielded two goat figures cast in solid bronze, dated in the 6th century B.C. (Mound 2, Tasmoly V burial). Hollow-cast goat figures decorate two handles from Murzashoka near Karakalinsk. A remarkable figurine of a ram occurs on an embossed bronze battle pick from Borovoye Lake area. In addition to a bone clasp shaped as a gryphon’s head (engraved on it is a deer surrounded by heads of other animals), Mound 3 at Tasmoly yielded gold plaques in the shape of a lion in side-view. Similar gold plaques were discovered in two other mounds of the same site. These images closely resemble the plaques from Tagisken and are dated in the end of the 6th century B.C.

Found in the Tasmoly I burial was a bronze plaque in the shape of an elk’s head; from a mound at Nurmanbet came the figured portions of a bridle (the protome of a wild boar carved from the horn of the Siberian stag). There is a full figure of a wild boar on a bronze plaque discovered near Karakalinsk together with the above-mentioned goat-shaped handles. There are many other finds from Central Kazakhstan with representations of animals, e.g. two bronze plaques made up of two goats’ heads (the mound near Lake Kairankul), the gold portion of a harness in the shape of the head of the saiga antelope (from the Turgai steppe), which is remarkably like the antelope figure from the Witsen Collection of Siberian relics. This collection, which has not come down to us, was amassed in the early 18th century, at the same time as the collection of Peter I. Another remarkable find is a cast bronze clasp with a crude representation of a beast of prey attacking a camel, which resembles somewhat the clasps with animals in conflict from the collection of Peter I. This clasp, found in a mound at Karamurun II burial ground, resembles in style the open-work bronze plate with birds from Mound 2 at Nurmanbet I. Both are dated in the end of the 1st millennium B.C.

The most striking finds in eastern Kazakhstan are those from the burial ground in the Chilikta valley, the northern foothills of the Tarbagatai Range. The mounds have wooden burial chambers. Mound 5 yielded gold plaques in the shape of a recumbent deer, a coiled beast of prey, the head of a bird of prey, a bird with open wings, wild boar figures punched in outline, and a fish-shaped gold casing. Found in Mound 7 was a gold plaque (a recumbent goat), plaques with birds’ heads resembling those from Mound 5, and a fish figurine punched in outline. S.S. Chernikov dates the former mound in the 7th century B.C., and the latter in the middle of the 5th century B.C. Analogous finds from the Northern Black Sea area lead us to date Mound 5 in the early 6th century, and Mound 7 in the second half of that century.

Several sets of cultic objects were discovered in Alma-Ata Region, Eastern Kazakhstan, and in Kirghizia around Lake Issyk-Kul. These include so-called altars — miniature bronze tables with legs, and lamps — trays on higher or lower supports. Placed along the edges of both are figurines of animals, sometimes locked in combat. The lamps carry figures of animals or people and have a tube for the wick in the middle of the tray. Special mention should be made of the Semirechye altar found near Alma-Ata, a lamp with a square tray from the same area, two altars and a pair of lamps from the village of Semenovskoye on the northern shore of Issyk-Kul, and a hoard found near the settle-

(270/271)

merit of Issyk, Alma-Ata Region (three bronze and one iron cauldrons and an iron altar). There are other finds of a similar nature. Two cauldrons from around Alma-Ata stand out because one is decorated with the protomes of winged goats and the other has legs in the shape of the head and shoulders of a mountain ram. These objects, connected with Zoroastrianism, are dated in the second half of the 1st millennium B.C.; they do not lend themselves to a more accurate dating. Stylistically, they resemble the bronze handle from the settlement of Khumsan (north of Tashkent) — a cylinder surrounded by figures of dancing nude women.

Two gold armlets were discovered in Duzdak (the Kara-Kum Desert). One armlet (of which only fragments are preserved) is of wire and bears a stylized figure of an imaginary creature with a horn of birds’ heads. The other (fully preserved) consists of two openwork plates held together with joint-pins; the figures of horses with inlay carry on the tradition of the Oxus treasure, but the armlet is dated considerably later. Of a still later date are the objects from the burial discovered in a rock crevice in Kargalinsk gorge, Alma-Ata Region. The figures with inlay on the long gold band (diadem) display motives of Chinese origin dating from the beginning of the new era.

Two parallel trends developed in Central Asian art: one clung to the traditions of antiquity in the realistic interpretation of the images, the other was marked by schematic tendencies of the Siberian animal style. The former trend is graphically represented by finds from Old Nissa, the Parthian capital (near Ashkhabad), whereas the latter is most clearly manifested in the Duzdak armlets.

III. Altaian Mounds. ^

In Maiemirskaya steppe, in the south of the Western Altai, bronze portions of a bridle were found back in 1911, together with gold plaques bearing stamped images of a colled beast of prey. These are considered the oldest specimens of Siberian animal art. Another Altaian find is the bronze mirror with engraved figures of standing deer in side-view, also dated in a very early period. Figures of animals carved in wood were discovered in the Altai even in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In 1865 V.V. Radlov dug up two of the Altaian burial mounds which contained finely preserved articles of wood and fur. But large-scale excavations of the mounds were undertaken only in the Soviet years, and they produced unique sets of articles in wood, felt, leather, textiles and other organic materials which ordinarily do not survive in graves.

That these materials were preserved in the Altaian graves is explained by the fact that the graves froze over soon after they had been constructed. The mounds, lying 1000 metres above sea level, were topped with boulders which served to condense the cold. In the course of the long rigorous winter the boulders froze so deeply that they did not thaw off during the summer. As a result, permafrost pockets formed under the boulders, encompassing the graves and their wooden burial chambers, the bodies of the deceased with the accompanying objects, as well as the bodies of horses (five to twenty-two in each burial) and the horse-trappings which were placed outside the chamber under cover of the same mound. The graves had been rifled before they were dug up; only those objects which were of no value to the plunderers, remained. The burials of horses, which were Inaccessible to the plunderers, remained intact. The finds therefore consist largely of horse-trappings.

Very few metal objects were found in the Altaian mounds because the plunderers were after these very objects. There is a pair of gold earrings, parts of a tubular copper collar (necklet) terminating in gryphon figures in wood and horn covered with gold, several silver and bronze plaques and two mirrors (a bronze one and a silver one with a handle of horn).

Mound 5 at Pazyryk contained two carpets buried together with the horses: a wool carpet of Iranian origin and a local felt carpet. The latter has a recurring pattern: a seated goddess and a mounted warrior in a wide cape. The remains of another felt carpet present a combat

(271/272)

between an imaginary (half-animal, half-human) creature and a bird. Depicted on some of the wooden pendants of the horse-trappings from Mound I at Pazyryk are human masks, whereas the leather pendants from the same mound represent people’s heads with animal ears and horns. Mound 5 also yielded fragments of Iranian textiles showing, in one case, a cultic scene and in another, a lion frieze. Found in Mound 3 were embroidered Chinese silks.

Of special interest among the numerous harness ornaments are the horses’ head-dresses. These are made of different materials and depict one animas attacking other animals. The same subject occurs in the metal ornaments for bridles from the Northern Black Sea area. The ornaments for horse-trappings in horn, wood and leather represent elks, deer, rams, goats, tigers, different birds and imaginary creatures. These are depicted both as complete figures and as heads, and are often combined with one another in decorative compositions which flow into plant or geometric motives. Most widespread are sculptures and reliefs, but there are also flat figures, especially appliques in felt and leather (on the saddlecloths the appliques mostly show one animal slaying another). Polychromic compositions are a characteristic feature of Altaian art: different materials and differently-coloured felt and leather are combined, gold and tin leaves and other means are employed. All the burials excavated in the Altai were constructed during a period of some 200 years and generally belong to the 5th and 4th centuries B.C.

Mounds resembling those of the Altai have been discovered in the Sayan Mts. Found in them were bronze, bone and horn objects with animal figures.

IV. Minusinsk and Ordos Bronzes. ^

The end of the bronze epoch in the Minusinsk lowland is represented by the Karasuk culture whose appearance is linked with the penetration of a new ethno-cultural element (most probably of Central Asian origin) into the local Andronovo culture milieu. The descendants of those newcomers are the Kets speaking a Tibeto-Burman language. Simultaneously with the spread of the Karasuk culture of Minusinsk Territory, new forms of metalware appeared in West Siberia and the Volga and Kama area — forms that were identical with those of the Karasuk culture, specifically bronze knives with sculptures on their handles, discovered in the Seimino burial ground on the Volga, the Turbino burial ground on the Kama, and recently in Rostovka village near Omsk. Karasuk art as such did not know these images: the handles of the knives were decorated with sculptured heads of animals. It may be assumed, however, that the Karasuk culture and the Karasuk-type knives with sculptures on the handles have a common origin.

The Karasuk culture traditions are traceable in the Tagarskaya culture which superseded it. The Tagarskaya culture abounds in forms similar to those found in the objects of the Saka period from the Altai and East Kazakhstan, which are devoid of any carry-overs of the pictorial art of the preceding period. The specific features of the Tagarskaya culture are largely due to the steady prevalence of bronze over iron. Bronze was used to make weapons, household articles, tools and ornaments, many of which were decorated with animal figures. In the early stage, sculpture in the round prevailed, but later it was superseded by work in relief which grew increasingly lower. Among the early objects are bell-shaped handles topped with goat figures or, less frequently, with deer figures. The handles of knives and daggers and the plugs of axes and other tools were decorated with smaller sculptures. The subjects of reliefs were mostly birds’ heads and coiled beasts of prey.

Nearly all the images from the Tagarskaya sites have obvious analogies in West Siberia and the Northern Black Sea area. Still, certain motives characteristic of Scytho-Sarmatian art appeared in the Minusinsk lowland at a considerably later date. Thus, the habitual early-Scythian motive of a recumbent deer is absent from both Karasuk and early Tagarskaya art; it spread in the latter not before the 5th century B.C. and acquired typically Minusinsk features. A number of other motives and details found their way into Tagar-

(272/273)

skaya art not before that time — moreover, showing traces of Altaian or East Kazakhstan origin. Ornamental motives that almost completely lost their representational elements— mostly stylised birds’ heads — also became widespread.

These novel subjects and forms remarkable for their dynamic quality and realism (despite obvious stylization), far from ousting early Minusinsk art, existed parallel with it. They began to occur in typically Minusinsk objects. The local craftsmen thus assimilated these subjects while continuing to work in the traditional Minusinsk slyle [style].

Found in the Minusinsk lowland were several bronze clasps resembling the gold clasps from the Siberian collection of Peter I. On some of them we see animals in conflict, on others symmetrically arranged animals in repose.

Having sprung from Karasuk roots in the 7th century B.C., the Tagarskaya culture persisted till the end of the 1st millennium B.C., being gradually transformed into the Tashtyk culture which clearly incorporates Hunnic-Chinese elements; at that time Mongolian features appeared also in the physical type of the population.

The Minusinsk lowland was an outlying province of Scytho-Siberian art, but it was not the boundary of the latter, which reached as far as North China. Beyond Lake Baikal the forms of that art are traceable in the graves with boxes of stones and the «deer stones» associated with the latter, which are also found in Tuva and North-Western Mongolia. Among the Trans-Baikal finds mention should be made of the unique clasp from Verkhneudinsk (Ulan-Ude), as well as the later-period objects from the Ivolginskaya town-site and the burials belonging to the same Hunnic culture. These include several bronze clasps resembling those of Minusinsk and several objects of Chinese origin. The Noin Ula mounds of Mongolia, which belong to the same culture and are close to it in time, yielded, along with motives carrying on the Scytho-Siberian tradition, also some objects testifying to the emergence of an independent Hunnic art (oval and figured silver plaques with yaks, deer and trees).

Many of the bronze objects with animal figures from the Ordos — a Chinese province in the great bend of the Hwang-Ho — reveal a close affinity with the works of Scytho-Siberian art, especially those from the Minusinsk lowland. These include objects dating from both the Karasuk and Tagarskaya periods. The appearance of such works in North China is connected with the penetration of the Yüeh-chih, the Central Asian unit of the Saka. The Yüeh-chih, who were later driven westward by the Huns, had managed to leave a distinct mark on Hunnic culture and even on the art of China. In later-period Hunnic art the motives and forms of Scytho-Siberian origin are combined with similar motives treated in the Chinese manner.

V. Siberian Gold Objects. Belt Clasps. ^

In the early 18th century the ancient burial mounds of West Siberia were rapaciously dug up with the only purpose of getting at the gold objects. Some of the gold articles thus obtained were collected on the orders of Peter I for his museum; thence they were subsequently transferred to the Hermitage Museum. This collection, known as Peter’s Siberian collection and numbering over 250 exhibits, had not been fully published until recently; most of the objects were not scientifically dated owing to the lack of definite chronological analogies. Only after the Altaian mounds had been excavated it became possible to distinguish the objects of the Siberian collection dated in the same period from those of a later period.

Among the earliest specimens of the collection is a massive plaque in the shape of a coiled beast of prey, corresponding to the earliest works of Scythian art from the Northern Black Sea area. The plaque is accordingly dated in the 6th century B.C. There are 14 pairs of open-work clasps and one half of a clasp (the other half was in the Witsen collection). Most of the clasps have one or two semicircular projections on the lateral side and, accordingly, have a P or B-shape. Others are rectangular, still others are figured. Typologically the P and B-shaped clasps are older than the rectangular ones, though

(273/274)

both types coexisted for a certain period of time. The two earliest clasps of the first group depict animals locked in combat — a gryphon and a horse, a griffin and a yak. In general composition and details they resemble the figures of the Altaian burial mounds. Other clasps of the same shape are indicative of artistic decay and deformation, which points to a more or less lengthy process of copying the originals. The copies were made with the help of a model taken from the original or, more ofren, they were obtained by pouring wax over its impression.

The first group of clasps includes two pairs showing, respectively, people resting in the shade of a tree and a dramatic hunting scene in the woods. They stand out not only because the composition includes human figures but also because they show the landscape connected with the scene. The second pair of clasps, moreover, has abundant inlay. In a number of features both pairs of clasps approximate the representation of the seated goddess and the mounted warrior on the felt carpet from Mound 5 at Pazyryk. Genre scenes with a landscape occur on bronze clasps from North China. One of them, discovered in Funghsi in a burial dated in the last quarter of the 3rd century B.C., enables us (taking into account the above-mentioned correspondence) to date the appearance of clasps with such compositions in the 4th century B.C. The scenes depicted are episodes from heroic legends and romantic tales popular in the Iranian world; according to Charitus of Mytilene (4th century B.C.), such scenes were to be found in temples and houses. The compositions on the clasps are reproductions of such scenes.

The bronze clasps from the Minusinsk lowland, the Trans-Baikal area and North China are copies of originals in gold, although only one gold clasp was actually found in this territory (in the Trans-Baikal area). That bronze clasps are traceable to gold ones, is borne out by the cavities for inlay, common in gold objects but not in bronze ones. The large number of bronze clasps available enables us to watch the transition from P and B-shapes to a rectangular shape without a setting, and finally with a setting. The gradual change of the clasps’ shape corresponds to the stylistic evolution of their images and of Scytho-Siberian art as a whole. This process can be ascertained also by comparing the scenes with animals in conflict on the applique patterns from the Altaian mounds and similar scenes on the carpet from Noin Ula. The trees depicted on the clasps with animal figures were stylized and gradually changed into antlers; on rectangular clasps they were shifted to the sides, changing into the plant design of the setting. The images became ornamental and schematic. Clasps with a geometric design appeared.

VI. Siberian Gold Objects. Collars and Armlets. ^

Collars (necklets) and armlets figure prominently among the gold objects of Peter’s Siberian collection. Some of them are made of wire, others are tubular. They are either annular (with unclosed or overlapping ends) or spiral, made of several coils. The tubular collars usually have several hoops soldered together and terminating in a semi-hoop. Because the tubes are hard, special devices were needed for putting them around the neck or arm. They consist of two detachable parts, held together either with a plug or a joint-pin.

The earliest tubular collar in the shape of a hoop with overlapping ends (terminating in lion-gryphons with inlay) consists of two parts held together in the middle with tiny nails, and at the back with a plug. It is a piece of Iranian jewellery of the 5th century B.C. Another collar of the same type, terminating in flattened lion figures, is most probably also of Iranian origin and dates from the same period. A characteristic feature of other detachable tubular collars is that their back part was fixed to the front part with two plugs instead of one. These are penannular collars; instead of overlapping ends they terminate in semi-hoops with animal figures. In addition to the collars made up of a hoop plus semi-hoop, the Siberian collection includes collars made of two hoops plus a semi-hoop, with plugs to hold together the detachable parts. The primitive character of these collars is strikingly manifested in their stylized images which pass into ornamented

(274/275)

terminals. By analogy with finds in Altaian and Sarmatian burial mounds, these collars are dated in the 4th-3rd centuries B.C.

Collars made up of several hoops (up to ten) are held together with the help of joint-pins instead of plugs. Stylistically they do not differ from the hooped collars with plugs; but they appeared not earlier than the 3rd century B.C. Collars consisting of hoops with semi-hoops are barbaric imitations of the spiral collars widespread in Western Asia in the Parthian period and known in the Bosphoran area and Thrace. The joint-pin locks came to prevail from the 2nd century B.C. The armlet with Joint-pins from Duzdak is apparently a piece of Graeco-Bactrian jewellery of the 2nd century B.C.

The greater part of the armlets are also penannular or spiral and are made of wire of different calibre. They differ largely in their terminals. There is a spiral collar of three coils with recumbent lion figures at the ends, whose forms and inlay closely resemble the tubular collar with similar figures.

Analogous sculptured figures are used to decorate wire armlets of seven or ten coils. A number of armlets made up of several coils date from an earlier time than the collars with joint-pins. Some of them bear figures of a beast of prey devouring some animal; only the head (or head and shoulders) of that animal protrude from the jaws of the beast of prey. This motive, which does not occur on the armlets in the Oxus treasure, can be seen in other works of Achaemenian-Persian origin. In Graece-Scythian art it began to spread in the 4th century B.C.

VII. Siberian Gold Objects. Jewellery, Horse-Trappings, Figurines and Vessels. ^

A plaque with rich inlay, shaped as a griffin with a goat in its talons, is in all probability a work of Achaemenian-Persian art of the 5th-4th centuries B.C. Some of its details resemble the bird struggling with an imaginary creature depicted on the fragment of the applique felt carpet from Mound 5 at Pazyryk. The round plaque with a beast of prey attacking an elk also dates from the same period as the Altaian burial mounds.

Earrings with pendants (found apart from the earrings) and finger-rings are prominent among the objects of the Siberian collection. The most common earrings are figures of eight made of wire with a small loop to which various ornaments were attached with the help of a chain.

Another group of earrings are hoops to which ornaments were soldered (diminutive hoops with pendants or clusters of beads attached to a hard core). Both kinds of earrings occur in the Sarmatian burials beginning with the 5th century B.C. The finger-rings are not many, and most of them have a solid hoop.

Animal figurines are either one-piece, or have the legs, ears and horns soldered to the body. All have horizontal pedestals attached to the feet. There are also three models of trees with branches and leaves, which were probably used, together with animal figurines, for cultic compositions affixed to some unknown objects. Some of the figurines closely resemble their Oxus counterparts of Achaemenian-Persian origin and are dated in the same period as the treasure of the Oxus.

The horse-trappings include falars, plates, tips, etc. Since falars do not occur in West Siberian and Altaian burials, it may be assumed that both the Graeco-Bactrian silver falars and the gold falars of the Siberian collection were discovered not in Siberia but in the steppes of the Volga and Don, where several falars of the same type were found (dated in the end of the 1st millennium B.C. and the beginning of the new era). Plates with onyx inlays and figures in high relief, resembling those from the Minusinsk lowland and the Trans-Baikal area, are probably of West Siberian origin and should be dated in the last centuries before the new era.

The handle of a vessel in the shape of a galloping deer from Bugrovaya Osyp, Bukhtarma River, is of Achaemenian-Persian origin, and so are the whole vessels from the Siberian collection.

(275/276)

VIII. Scytho-Siberian Animal Style. ^

Three areas of Scytho-Siberian art are distinguished. One is the Northern Black Sea area with the North Caucasus, the other is Central Asia with the contiguous part of West Siberia, and the third incorporates the easternmost regions including the Minusinsk lowland, the Trans-Baikal area, Mongolia and North China. However, the earliest works of Scytho-Siberian art are traceable not to any of these areas but to north-western Iran (the Sakiz treasure). This hoard includes, in addition to Assyrian, Urartaean and Manneian objects and art forms from the Ancient Orient, works bearing a distinctive imprint of the Scythian style.

Scytho-Siberian art crystallised when the Iranian tribes of Western Asia borrowed and reinterpreted the images and subjects of the art of the Ancient Orient. At first its distinctive character could be seen only in the selection, from the rich stock of Oriental art, of those images that appealed to the barbarians confronted by a superior culture, and in the reinterpretation of these images in keeping with the barbarians’ requirements and technical means. This art spread rapidly among the tribes of the Northern Black Sea area, Central Asia and Siberia — tribes that were kindred to the Iranians of Western Asia. The affinity of the animal styles of the Northern Black Sea area and Siberia, on the one hand, and certain differences in the treatment of identical subjects, on the other, leave no doubt as to the common origin of both and to the independent development of art in each territory.

Scytho-Siberian art selected few animal figures out of the rich stock of the Ancient Orient: the goat and the deer (the head or whole figure) in the traditional sacrificial position, lying with turned-down legs so that the hooves of the forelegs and hind legs are superposed; standing or walking goats and deer are depicted far less frequently (with the legs seemingly suspended and the sharp ends of the hooves turned downwards). The horse was symbolised by its head; sometimes the head had long ears to indicate that a mule or donkey was depicted. Representations of the bull, even of the bull’s head, are extremely rare. Much more frequent are rams’ heads, heads and figures of the wild boar, and occasionally the hare. Among the beasts of prey, early Scytho-Sarmatian art favoured the panther, which was spread in the north of Western Asia and the Transcaucasus. There are walking, crouching and coiled panther figures. But the lion, so widespread in the East, does not occur frequently and is often represented only by the head. There are bird images — heads in side-view and figures of birds with closed or open wings. Among the fabulous creatures, gryphons were popular in early Scytho-Siberian art. In the Northern Black Sea area and Siberia the elk, bear and wolf were added to this gallery.

Scytho-Siberian art hardly has any compositions with two or more figures. There are only the simplest representations of pairs of animals in the reversed-image manner, which may be conventionally termed heraldic. In early Scytho-Siberian art the animals were depicted in repose — walking, recumbent or standing, sometimes with the head turned back. Neither were there any images of anthropomorphic deities characteristic of the Ancient Orient. This is most probably accounted for by the more primitive religion of the tribes among which this art was widespread. Scytho-Siberian animal art appeared in Central Asia and Siberia in the 6th century B.C., perhaps at the end of the 7th century. Works of this art were found in the burial grounds of Tamdy, Tagisken, the mounds of Central and East Kazakhstan and the Altai. They spread in the Minusinsk territory, reaching the Ordos as early as the 6th century.

From the 5th century B.C. the character of Scytho-Siberian art began to change: many motives disappeared or degenerated, with new ones taking shape. Among the extinct motives was the sculptured head of a bird-like creature with horns, extremely rare in Siberia but popular in the Northern Black Sea area. A coiled beast of prey was still depicted occasionally, but it assumed all the features of decay. The new period in the history of Scytho-Siberian art is most strikingly represented by objects from the Altai burials with frozen graves. This period is characterised by dynamic, highly expressive

(276/277)

images, the prevalence of compositions showing animals in conflict and also by the growing ornamentalism, with corresponding stylization of forms.

The reinterpretation of the borrowed motives which began as soon as Scytho-Siberian art took shape, resulted in the 5th century B.C. in the partial replacement of such animals as the lion and the panther by the tiger, well known in Central Asia and Siberia, and the ubiquitious wolf. Local variants of imaginary creatures appeared; these incorporated parts of bodies of different animals, but were almost invariably dominated by the Oriental gryphon. The elaboration of an animal figure with additional figures set into some part of the body, typical of Scythian art of the Northern Black Sea area, did not develop on an equal scale in Siberia. The only additional details used to enhance the main figure were birds’ heads attached to the ends of horns and tails (only when imaginary creatures were depicted). There is just one case of zoomorphic transformation in a developed form from Siberia — the gold clasp from Verkhneudinsk (the Trans-Baikal area).

In contrast to the Northern Black Sea area, scenes of animals in conflict are prominent in Siberian art. These have complex compositions and involved foreshortening indicative of a long period of evolution. Such scenes were derived from Western Asian Graeco-Persian models, which Siberian art assimilated in a strongly reinterpreted form. First and foremost, the foreign images were replaced by local ones — e.g. the lion by the tiger or wolf, the bull by the elk. Moreover, scenes of animals locked in combat were enriched in Siberian art with realistic elements, and they are more expressive and dynamic than their Iranian prototypes.

The masks (horses’ head-dresses) from the Pazyryk mounds also present combat scenes. There are abridged versions of these scenes, showing only the head of a beast of prey from whose jaws protrudes the head (or the head and shoulders) of another animal.

In the 5th century B.C. figures of animals with contorted bodies in violent motion replaced those in repose. The dynamic nature of Siberian art is seen also in the general treatment of images (curved forms and lines). Accordingly, the leading position was assumed not by sculpture in the round but by relief and flat painted or drawn figures. The details were treated in a conventional, ornamental manner using a system of curvilinear signs and contrasting colour patches. Particularly widespread was the technique of emphasising certain parts of the body with special signs — figures of eight, circles, dots, crescents, curved triangles and spiral scrolls, etc. These geometric figures were used to accentuate the shoulders, hips, muscles and other protruding parts of the bodies of animals. They were also popular in the art of Achaemenian Iran. On textiles, carpets and jewellery the details were accentuated with colour (in the case of jewellery, with inlay).

The «inlay style» common in Central Asia and Siberia emerged as a result of the interaction of carpet- and textile-making and the goldsmith’s craft. This style, represented mostly by applique designs on felt and leather objects from the Altaian mounds, imitated in a simplified form the style of carpets and textiles and was influenced by the local goldsmith’s craft just like the jewellery and textiles of Iran.

In keeping with the decorative purpose of Scytho-Siberian works of art, the ornamental treatment often dominated the entire scene to the detriment of the subject. Specimens of this art demonstrate how the figure of an animal or its details were stylized, resolving into an ornamental motive. In addition to animal designs, plant designs began to be used: the lotus, rosette, palmette, running spiral and creeping vine, which appeared both separately and in combination with other forms. The Western Asian origin of the plant designs in most cases is beyond any doubt.

The ornamental trend, apparent above all in the perfectly symmetrical compositions and, subsequently, in the stylized images (which can be seen in the later specimens of Peter’s Siberian collection and the bronzes of Minusinsk territory, the Trans-Baikal area and the Ordos) resulted ultimately in the suppression and ousting of the realistic as well as all representational elements in Scytho-Siberian art. As a result of constant repetition, the

(277/278)

animal figures became increasingly crude and geometricized, with certain features emphasised to the detriment of the whole; ornamentally treated fantastic images came to the fore. Coloured inlay, which used to be auxiliary, became an independent decorative component and gradually superseded representational motives. The foliage design derived from the trees and branches in the landscape compositions, lost its plant elements and became abstract. Its forms penetrated into inlay work of every kind. Ultimately, the Scytho-Siberian animal style was superseded by the new geometric polychromic style, with jewellery dominated by diverse inlay (gems and glass paste).

Apart from the decoration of household objects, Scytho-Siberian art had a definite cultic purpose. Animal figures or parts of these figures served as amulets, and also as personifications of cosmic forces; these two purposes did not clash, however. The figures were intimately linked with the myth of the people; they reflected the ideas of good and ill, of life and death and the struggle between these opposites. In this context the barbarian tribes adopted the figures of real and imaginary animals current in the art of the Ancient Orient and reinterpreted them in keeping with analogous local beliefs, in which the totemic traditions still persisted. The anthropomorphisation of images taken from mythology was a new phenomenon in Scytho-Siberian art and it signified not only a personification of the forces of nature but also a deep-going process of social differentiation.

Mythological images played another important role as they appeared on ornaments denoting social rank; their original meaning was thus obscured and distorted under the impact of decorative, artistic requirements. Religious subjects turned into everyday subjects. There appeared genre scenes, specifically episodes from Iranian epics and poems, borrowed mainly from the monumental art of Western Asia.

[ IX. ] * * * ^

The history of art in Siberia in the Scythian or, more accurately, Saka epoch can be divided into three periods. The first period, dated in the 6th century B.C., witnessed the rise of the animal style. The second period may be termed the Achaemenian period, since the development of Scytho-Siberian art at that time was dominated by the Persian impact, although it was highly distinctive because of the barbarians’ creative reinterpretation of Western Asian models. Subsequently, in the Hellenistic period (the last centuries of the 1st millennium B.C.) when the Graeco-Bactrian Kingdom came to the fore in Central Asia, the realistic traditions in Scytho-Siberian art were undermined by ornamental stylization — in spite of the continued influence of the hellenised Orient.

In the eastern zone of Scytho-Siberian art, which the Huns dominated from the 3rd century B.C., this art persisted till the beginning of the 1st millennium A.D. in ever more crude copies of the earlier models and was gradually ousted by forms of Chinese origin. But in the steppes of the South Urals, the Volga and the Don, where part of the Iranian-speaking peoples of Central Asia and West Siberia migrated, Scytho-Siberian art continued to develop in close connection with the Hellenistic states of Central Asia and the Greek poleis of the Bosphorus, and for some time it was able to resist the purely decorative trend. As a new phase in the history of the animal style, it became the basis of the distinctive Sarmatian art.

|