S.J. Rudenko

S.J. Rudenko

The mythological Eagle, the Gryphon, the winged Lion and the Wolf in the Art of Northern Nomads.

// Artibus Asiae. 1958. Vol. XXI, 2. P. 101-122.

Published by agreement with the Institute for the History of Material Culture, Moscow

In the second and third quarters of the first millennium B.C. numerous cattle-breeding tribes, similar in habits and culture, inhabited the vast steppes, hill-lands, and semi-deserts that stretch from the Carpathian mountains in the west to Mongolia in the east.

The names of these tribes are known to us from Grecian, Assyro-Persian, and Chinese sources. The areas north of the Black Sea up to the river Don as well as the lands north of the Caucasus were inhabited by different so-called Scythian tribes. The Sauromatae, who according to Herodotus spoke a language originally Scythian but long since corrupted, dwelt east of the Don. The Iyrcae lived east of the Urals; and the territories still further eastward, close to the high mountains, were inhabited by the Argippaei, who as the same historian tells had separated themselves earlier from the royal Scyths. The Upper Irtish and the Altai were inhabited by the legendary Arimaspi, the “gold-watching griffins”, or the Yüeh-chih of the Chinese sources. The Hsiung-nü and the Tung-hu dwelled to their east. In Middle Asia there thus lived different Sakian tribes, to the south and west of whom resided the civilized peoples of the Near East.

Herodotus’ testimony that the same tribes of Eastern Europe and Western Asia were called Scythians by the Greeks and Sakians by the Persians, is of great value. From the anthropological point of view they were all Europeoids and spoke different dialects of the North Iranian linguistic group. The Hsiung-nü and Tung-hu were Mongoloids, and their languages were Turkish and Mongolian respectively.

Notwithstanding the nomadic way of life of these ancient cattle-breeding tribes, they may be called nomads only with many reservations. First, the Scythian tribes located on the northern shores of the Black Sea were characterized as husbandmen and ploughmen by Herodotus. Second, the vast majority of the tribesmen had stationary winter settlements with small sowing areas attached, and so should more properly be called semi-nomads.

The breeding of livestock, especially of horses, was the chief occupation common to all inhabitants of the Euro-Asiatic steppes.

Besides the probable kindred of the Scytho-Sakian tribes and their decidedly Asiatic origin, the absence of natural impediments on the tremendous territories which they occupied and their nomadic habits largely contributed to their mutual intercourse and to the formation of one and the same economy and of one and the same social organization — military democracy, as well as to the same culture and ideology.

The excavations of the large Altaian kurgans pertaining to the Scythian epoch showed that the customs of the ancient Altaians were similar to those circumstantially described by Herodotus as belonging to the Black Sea Scyths, i.e. scalping of the slaughtered enemy, embalming

(101/102)

of corpses of tribe leaders and burying of their concubines with them, expiation ceremonies with burning of hemp etc.

The cultural community of the Scytho-Sakian tribes found its most distinct expression in their art. One of the characteristic features of that art is the so-called “Scythian animal style” which manifested itself in a peculiar manner of representing animals.

On such a vast territory with various populations there could not but exist local distinctions. They were caused by different epochs, characteristics of the material used, individual traits and talents of the artisans and finally by foreign influences.

Similar motives and methods of creative work and a number of details specific of the Scytho-Sakian art serve as a convincing proof of the cultural community of the Scytho-Sakian tribes in the VII-IV centuries B.C.

The Turko-Mongolian horse-breeding tribes of Central and Eastern Asia contemporary to the Scytho-Sakian tribes developed under different historical conditions, and their art naturally differed from that of the Scytho-Sakian tribes. The way in which the Scytho-Sakian art influenced the art of these eastern neighbourly tribes is nevertheless a clear proof of the intercourse between those groups of tribes diverse in their origins.

Substantial material, still published only in part, is a great help in judging the art of the Black Sea Scyths.

The art of the tribes that inhabited the prairies of Western Siberia is best represented by the Scytho-Sakian collection of Peter the Great in the Hermitage, the greater part of which consists of objects belonging to the Scythian epoch. The so-called “Treasure of the Oxus” affords an idea of the art of the Middle Asiatic tribes. The art of the cattle-breeding tribes of Mongolia and of Northern China is represented by the rich collections formed by C.T. Loo and the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities in Stockholm. Recent archaeological excavations have given ample proof of the richness and diversity of the fine arts of the Altaian tribes.

Many works have been devoted to these arts. M. Rostovtzeff [1] and K. Schefold [2] have dealt primarily with the art of the Black Sea Scyths. G. Borovka [3] and E. Minns [4] have treated Scythian art on a larger scale, including also the art of the Asiatic horse-breeding tribes. The most remarkable objects of Peter the Great’s collection have been discussed by A. Salmony in a series of articles. [5] The Middle Asian collections have been minutely described by O.M. Dalton [6]; while studies have been devoted by J.G. Andersson [7] and by Salmony [8] to those from Mongolia and Northern China. One of the chapters of my book, The Culture of the Population of the Altai Mountains in Scythian Times (1953), is devoted to the art of the Altaian tribes. No general work has appeared that embraces both the art of the ancient nomadic tribes of Eurasia and that of the Altaian and Western Asiatic tribes, the last of which has become known only during the last decades. [9] The task of filling in this gap is one that I do not care to undertake here.

(102/103)

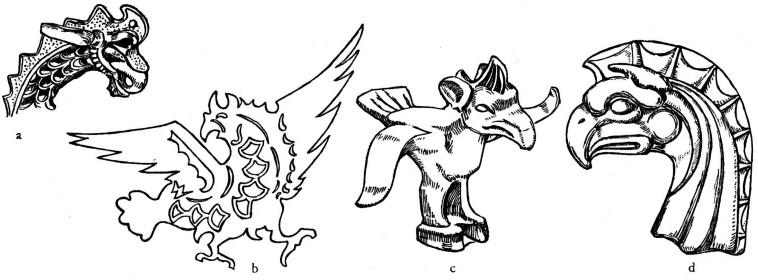

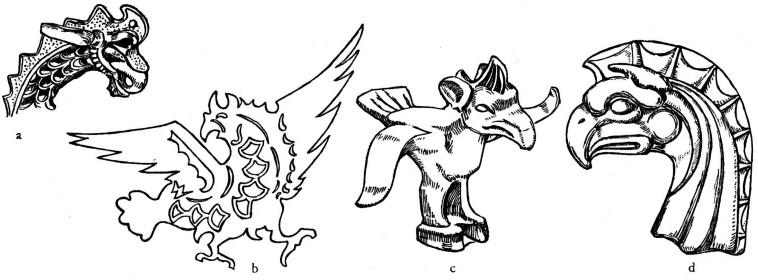

Fig. 1 (a) from gold cloisonnee placque, collection of Peter the Great, Hermitage; (b) saddlecloth ornament from first Pasirik kurgan; (c) copper eagle from sarcophagus, Berel kurgan; (d) silver eagle head from Seven Brothers kurgan.

(Îòêðûòü Fig. 1 â íîâîì îêíå)

In this paper I intend to draw the attention of the reader only to four of the numerous motives of the art of the Euroasiatic horse-breeding tribes of the middle of the first millennium B.C. These motives are: the mythological eagle, the gryphon, the winged lion, and the wolf. I have chosen these motives for the reason that the features common to all the tribes as well as the local stylistic peculiarities have been better expressed in the representation of those semirealistic and semi-fantastic animals than in the rendering of real animals.

*

By a mythological eagle I mean an eagle with large ears, a crest and sometimes a small forelock, a representation highly typical of the Euroasiatic horse-breeding tribes. Highly remarkable is the fact that the treatment of eagles from the northern shores of the Black Sea are known in many varieties, whereas they are extremely rare in the regions inhabited by the Asiatic tribes. Such eared and crested birds, on the contrary, are scarce in the Black Sea region as compared with Western Siberia and the Altai. The best and most diversely treated creatures of the sort are of Asiatic origin.

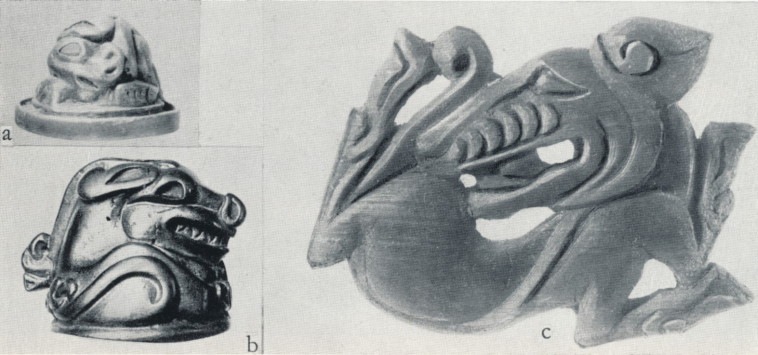

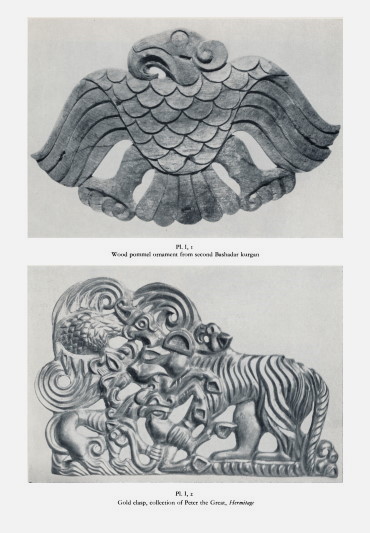

Remarkable for their force and monumentality are ornaments on pommels, carved in wood and having the form of an eared eagle en face with head turned back. They are from the second Bashadar kurgan in the Altai dating back to the end of the VI century and the beginning of the V century B.C. (pl. I, 1). The head of the eagle has no crest, the wings are spread and slightly drooping, the tail is unfolded. The mighty paws attract special attention. The treatment of the plumage by scales partly covering one another and forming a kind of coat-of-mail is highly typical. Identical is the manner of treating the feathering on the neck and on the breast (fig. 1a) of the eagle of the Siberian collection of Peter the Great in the scene “The Ibex in the Eagle’s Clutches”. [10] The posture of the Bashadar eagle is similar to that of the one on the gold plaque of the Treasure of the Oxus, [11] but the latter shows less force and monumentality.

Tiny eagles carved in wood and serving as ornaments of horse-trappings from the first Tuektin [Tuekta] kurgan in the Altai, of the same epoch as the second Bashadar kurgan (fig. 4b) have a number of features common with the big Bashadar ones. [12] Similar is the treatment of the heads

(103/104)

with large ears, but no crest. The manner in which the flight-feathers of the wings and the feathers of the tail are represented is the same, but the paws are lacking and the plumage of the breast and of the outer part of the wings is not shown either. As far as composition goes the tiny Tuektin eagles have much in common with the small gold birds from the Litoj Scythian kurgan of the Kiev group dating from the end of the VI century B.C. [13]

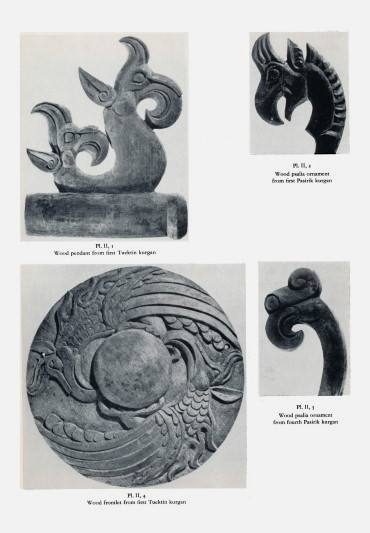

Wood-carved ornaments of horse-trappings from the same first Tuektin kurgan are very peculiar. They are: a pendant in the form of conventional eared eagles with a hooked beak, a small tuft and a tail terminating in a eagle’s head (pl. II, 1) and a frontlet with two eagles on it (pl. II, 4). From the point of view of composition, eagles with a small eagle head at the end of the tail are reminiscent of the gold Assyrian belt-clasp representing a lion with a small lion’s head at the end of its tail, published by A. Roes. [14] The wood-carved eagles on the round frontlet are remarkable from several viewpoints. We are as much impressed by the skill with which the figures of the two eagles are inscribed in a ring form round the hemispherical protuberance in the centre of the frontlet as by the clearness of the carving of the plumage on the breast, in the form of fine applied cloisons, and of the flight-feathers of the wings. Finally, comes an unusual treatment of the crest as a deer’s horn.

We meet with another interpretation in the eared eagles of the Siberian collection in the scene of the «Combat for the Prey» repeatedly published.

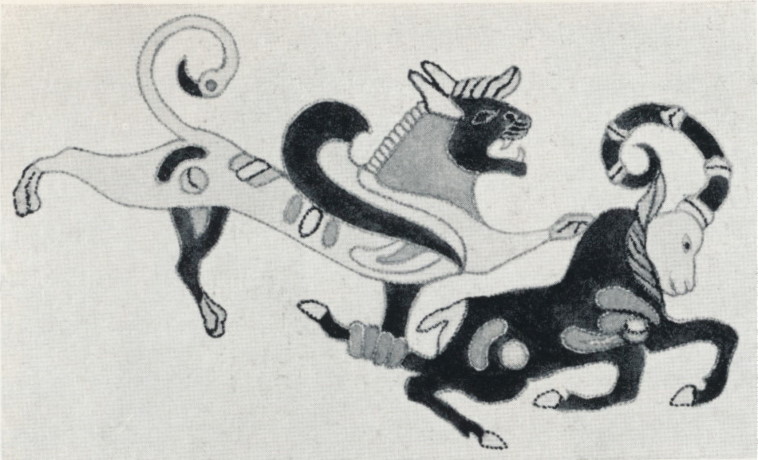

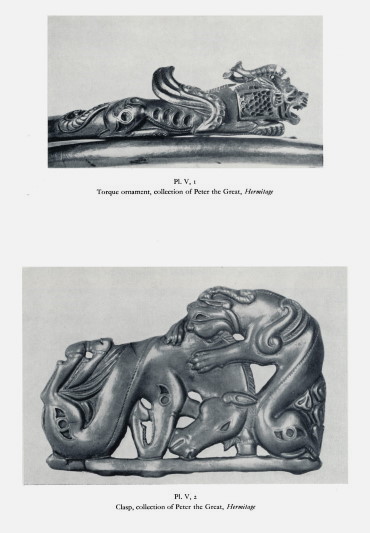

In one of these scenes (pl. I, 2) on the gold fastening of a garment, the victim is a monster with a body of a steed, the head of an eared and crested eagle and a cat’s tail with a small eagle’s head on its tip. The prey is attacked by a mythological wolf biting into the body of the monster and having caught hold of its tail; by a tiger biting into the body of the prey and holding its hind limb with the paw; and by an eagle clutching the head of the victim with its paw and simultaneously plunging its beak into the skull of the tiger. The spiral twist of the ear, the wings and the tail are highly typical.

The figure of the eagle in the scene “An Elk in the Eagle’s Clutches” seems to symbolize the might of this king of birds. It serves as an ornament of one of the saddle-cloths from the first Pasirik [Pazyryk] kurgan (fig. 1b).

I date the group of the large Pasirik kurgans from the V century B.C. The earliest of them, viz. the first and the second were erected in the same year, the latest — the fifth, having been erected 48 years later than the first two. The third and the fourth come in between. [15]

This eared eagle, shown as though hovering in the air with lowered wings, has a mighty crest and a small forelock and it is typical of the Altaian eagles. The feathering of its neck and breast is conventionally rendered by fine applied cloisons.

The small sculptural copper-cast figures of the eared eagles with small forelocks ornamenting the Block sarcophagus of the Berel kurgan in the Altai (fig. 1c), which approximates the Pasirik kurgan in date, are treated schematically.

While the Scyths of the northern shores of the Black Sea had comparatively few representa-

(104/105)

tions of the mythological eagle itself, eagle’s heads are rather numerous with them. The head of an eagle — a bronze pole-top from the large Ulski kurgan of the Kuban group (the beginning of the VI century B.C.) — is highly expressive. The bronze head of an eagle from the kurgan near Zourovka is very characteristic. The wood-carved head of an eared eagle with a crest and a small tuft (pl. II, 2) used as an ornament to the psalia found in the first Pasirik kurgan might serve as a parallel to the first (Ulski) whereas the carved head of an eagle adorning another psalia from the fourth Pasirik kurgan (pl. II, 3) is similar to the second (the Zourovka one). The treatment of the latter (pl. II, 3) is of interest from the point of view of its conventionality.

Special attention should be paid to the small silver head of an eagle from the Seven Brothers kurgan (fig. 1d) having a crenellated crest similar to that of the eagle from the first Pasirik kurgan (fig. 1b) and of the eagle of the Siberian collection (fig. 1a).

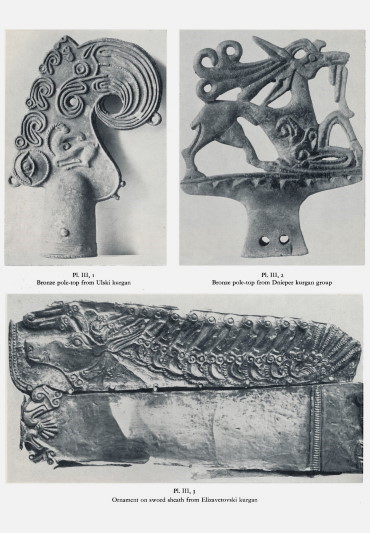

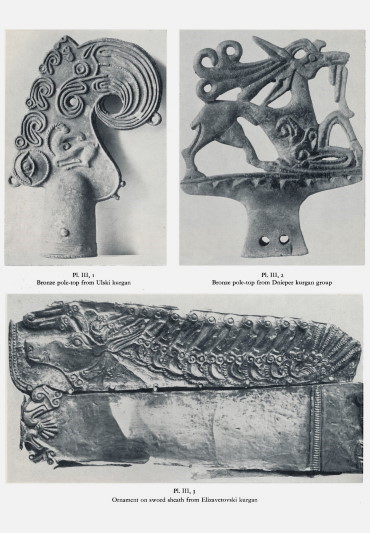

Great originality is displayed in the bronze-cast pole-tops from the Ulski kurgan, having the form of conventional eagles’ heads. The most interesting one among them is reproduced on pl. III, 1. This head has a human eye. The sere is marked by a row of small conventional eagles’ heads. The mighty beak twisted in a spiral forms the body of the creature whose eared head is placed under the sere of the main eagle. The figure of an ibex with head turned back, with doubled-up legs and a small bird’s head on the neck, that we see on the jaw of the eagle is very characteristic of the Scythian art in its early period.

Very often small eagles’ heads were placed at the ends of the horn branches of a deer or of an elk; sometimes they were even substituted for the horns. The gold plaque with the figure of a deer from Ak-Mechet in the Crimean group, belonging to the V century B.C., [16] or the head of a deer on the gold plaque ornamenting the sheath of a sword from the Elizavetovski kurgan of the Don group, V century B.C. (pl. III, 3) with horns presented by continuous rows of small eagles’ heads, may serve as examples. It is worth noting that a small eagle’s head is also placed on the neck under the lower jaw of the deer’s head accentuating its lower brim. On the plaque of the same ornament two heraldically placed eagles’ heads with a palmette between them are reproduced under the head of the deer. The peculiarity of the small heads consists in their forming a composition of two heads, the eye of one (the larger) being placed inside the whorl of the beak of the other (the smaller).

On the northern shores of the Black Sea mythological eagles’ heads with a palmette between them were substituted for the horns on small elks’ heads. For instance, small bronze-cast elks’ heads — the ornament of horse-trappings from the kurgan near Chigizin of the Kiev group, VI-V centuries B.C. [17] As an ornamental motive aiming at emphasizing the shape of the shoulder, small eagles’ heads were often used on the northern shores of the Black Sea on the figures of deer and other animals. The deer — a bronze pole-top from the kurgans of the Dnieper steppes, V-IV centuries B.C. (pl. III, 2) — on whose shoulder a small eagle’s head is quite distinctly seen, may serve as a striking example.

Small eagles’ heads as an ornamental motive in representing animals were widespread in South Siberia. They constituted one of the main artistic motives of a pair of gold belt-clasps from the Siberian collection. [18] We also see them terminating the tail of the fantastic animal and

(105/106)

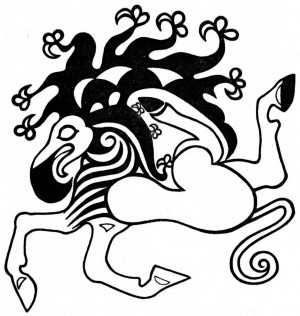

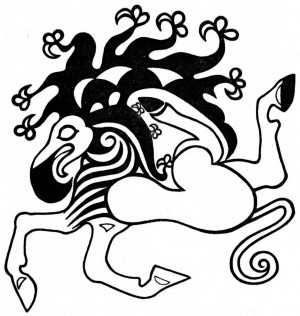

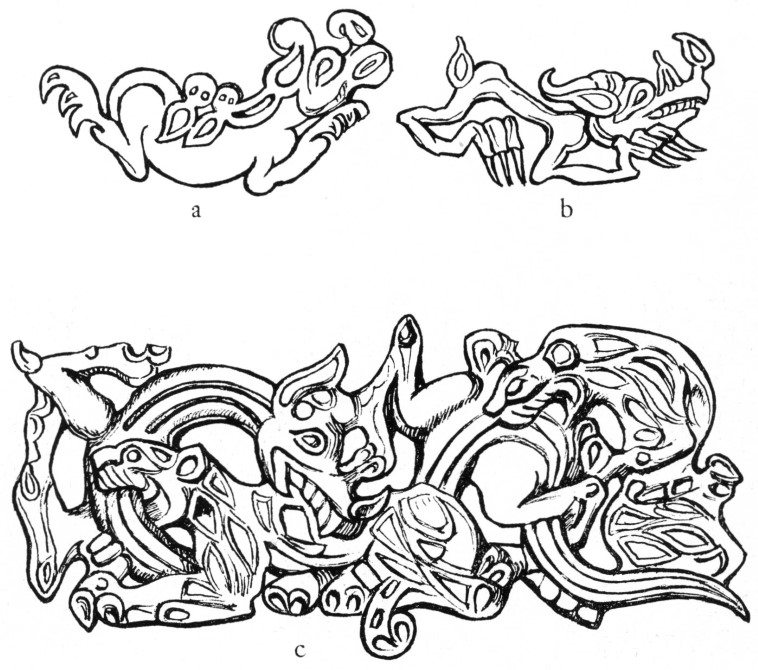

Fig. 2. Tattoing motif from second Pasirik kurgan.

(Îòêðûòü Fig. 2 â íîâîì îêíå)

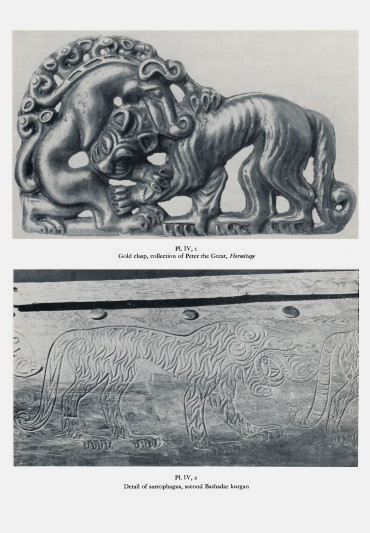

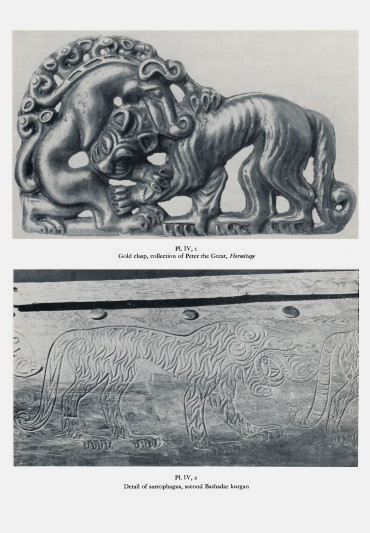

on the withers of the tiger in the scene of the Combat for the Prey (pl. I, 2). Small eagles’ heads represent the horns of the mythological wolf and we see one of them on the tip of the tail in the scene of the combat of the wolf and the tiger forming the clasp of a garment of the Siberian collection (pl. IV, 1).

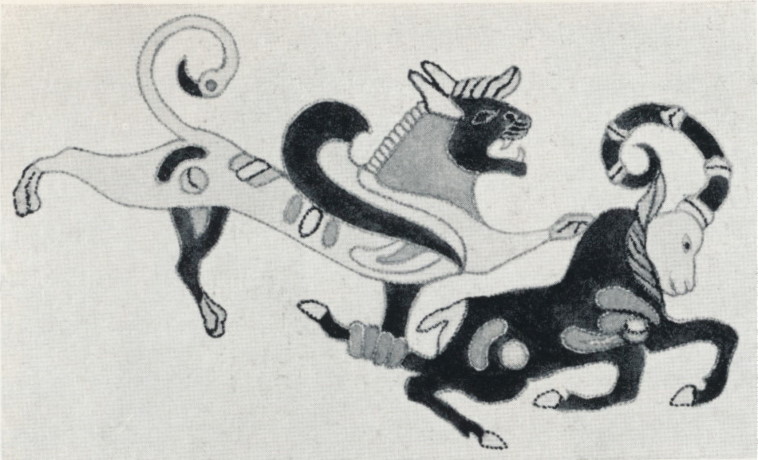

The body of the chief of a tribe from the second Pasirik kurgan was covered with tattooed representions of different fantastic animals, small eagles’ heads being widely used for rendering those animals. One of the latter (fig. 2) has the body of a deer, the beak of an eagle and the tail of a cat. Eagles’ heads are not only found on the ends of the branches of the horns, but also on the mane and on the tip of the tail.

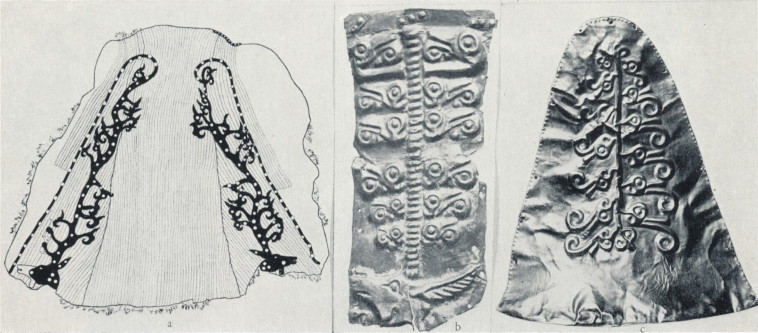

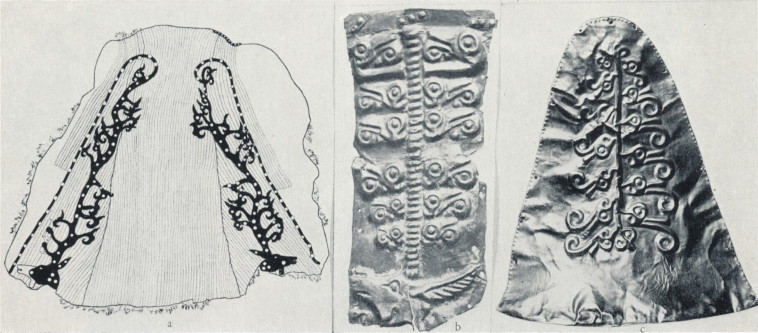

This ornamental motive was so widely spread among the horsebreeding tribes of Euroasia that garments and other objects were also ornamented with small eagles’ heads. On the right side of one of the garments found in the second Pasirik kurgan leather heads of deer with huge horns were embroidered, the branches of the horns ending in eagles’ heads (fig. 3a). Gold disks were inlaid instead of eyes. In one of the Scythian kurgans near Zourovka of the Kiev group, VI-V centuries B.C., a punched gold plaque was found having a deer’s head represented on it with horns rendered in conventional seamed lines with rows of small eagles’ heads along both sides of the lines (fig. 3b). On a similar plaque ornamenting a quiver from the Karagodeushkh [Karagodeuashkh] kurgan of the Taman group, IV-III centuries B.C. (fig. 3c), the head of the deer disappears and its horns are conventionally represented by two rows of small eagles’ heads.

The manner of representing mythological eagles’ heads varied naturally in accordance with the material, the destination of the object, and local traditions. Highly significant is the fact that those small heads as one of the artistic motives were universally spread among the Scytho-Sakian tribes and were similar in composition everywhere.

*

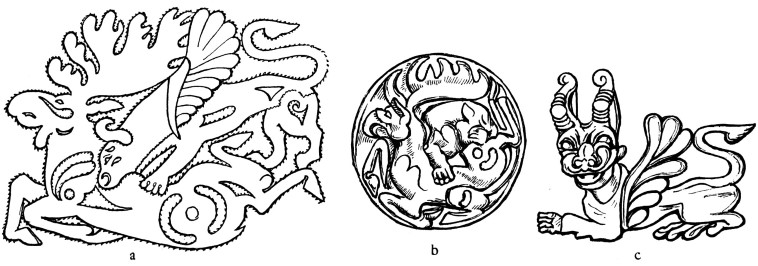

Like the eagles, the gryphons occupied a remarkable place in the art of all Scytho-Sakian tribes and had the same local peculiarities that were inherent to the treatment of eagles’ heads. Thus forelocks on the heads, as we shall see below, were the characteristic feature of the Altain gryphons.

Gryphons from the northern shores of the Black Sea are known to have been found in kurgans of different epochs. Substantially differing from one another, they all had one stylistically common feature — the body of a lion with four lions’ paws, an eared head with a crest all along the neck, and raised wings.

The gryphon in the scene of its attack on a deer — a punched gold plaque from the Ulski kurgan — and the gryphon on the silver mirror from the Kelermes kurgan [19] are the earliest representations of the kind. In the gryphon from the Ulski kurgan, special attention should be paid to the pronounced crest and to the flight-feathers of the lifted, reverted wings. As distin-

(106/107)

guished from the gryphon of the Ulski kurgan, the tail of which droops and passes between its hind legs, all the other versions from the northern shores of the Black Sea, the gryphon of the Kelermes kurgan included, have recurved tails terminating in a tassel. The Kelermes gryphon has a half-open beak and the flight-feathers of the wings point forwards.

Punched gold gryphons from the kurgan near Shpola [Smela] of the Kiev group, IV century B.C. [20] as far as style goes, differ considerably from the above-mentioned examples. The treatment of the head and of the body; the shape of the wings with flight-feathers turned forward; and especially the crenellated crest of the design of the Grecian representations of hippocamps indicate that they were created under the influence of the Grecian art.

In Western Siberia there is a pair of massive gold clasps belonging to a garment with a scene of a mythological wolf and gryphon attacking a lion or tiger. [21] The gryphon has an eared eagle’s head but the crest is lacking. The wing is treated like that of the eagle in the pl. I, 2.

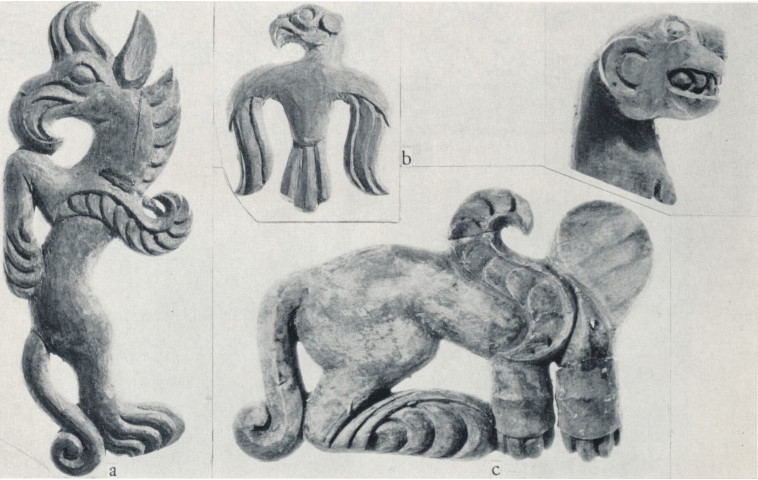

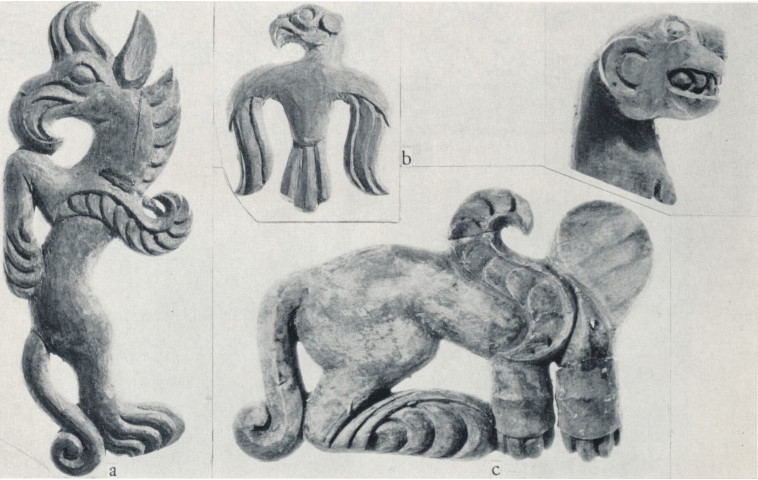

Several representations of the gryphon were found during excavation works in the Altai. The most characteristic ones may be seen on the saddle-cloths from the first two Pasirik kurgans. [22] Originality of composition is apparent in the wood-carved gryphon ornamenting the horse-trappings from the first Tuektin kurgan. The hind part of its body is reversed (fig. 4a). It is similar in composition with the gryphon of the gold armlet from the Treasure of the Oxus. [23] Its massive head has a strongly twisted beak, a forelock, an ear and a crest, all being well pronounced. The wing is twisted in a spiral with its end turned forward. The gryphon in the scene of its attack on an ibex on the polychrome felt saddle-cloth from the first Pasirik kurgan is remarkable for its wings directed backward, for a stripe on the breast seen from under the wing and imitating the woolly lower part of the lion’s belly, for a comma and a point on the croup and for a triangle on one of the hind legs. [24] A circumstantial description of these details will follow.

Two famous gold armlets with gryphons are known to have come from Middle Asia. One of them is from the Treasure of the Oxus and is described in detail by Dalton. [25] The second belongs to the Victoria and Albert Museum, South Kensington. The gryphons of these armlets have a slightly open beak, a hardly noticeable forelock and a weakly pronounced crest, whereas the ears are large. The hind legs are those of an eagle, while the body belongs to a lion. The wings are slightly raised and their flight-feathers are pointing forward. The plumage of the breast and of the wings, except the flight-feathers, are represented by fine applied cloisons. The peculiarity of these gryphons consists (I) in their ibex-like horns terminating in small cups; (2) in a small horse-shoe with sharpened ends placed on the fore-paw; (3) in a small mane on the lower part of the belly protruding from under the wing; and (4) in a point and two halves of a horse-shoe on the croup.

The well-known lion-gryphons on the frieze of the polychrome tiles in Susa are an essential help in dating the gryphons of the above-mentioned gold armlets. [26]

(107/108)

The gryphons from Susa have as low a crest, a wing of exactly the same shape, a small horse-shoe with sharp ends on the forepaws, a stripe of the woolly lower part of the belly protruding from under the wing, and two brackets on the croup.

Though a number of characteristic features are common for representations of gryphons from the northern shores of the Black Sea, for Eastern Siberia and for the Altai, the Altaian examples have a closer resemblance with the Middle Asiatic and Near Eastern ones in certain details mentioned above. In early Scythian monuments, such as in the Litoj and Kelermes kurgans, there are monsters treated in the clearly Near Eastern (Assyrian) manner, this being true particularly of the winged lions. However on the northern shores of the Black Sea the winged lions and the lion-gryphons in the treatment common to the Euroasiatic horse-breeding tribes appear comparatively late and are very scanty.

The lion-shaped punched gold plaque from the Seven Brothers kurgan apart from the lifted wing is of special interest as it has a small bird’s head instead of a tassel on the tip of the tail. [27] This detail which is found in representations of fantastic animals in Upper Asia at least two millennia B.C. grew to be later on a characteristic trait of the art of the horse-breeding tribes especially in Western Asia. The «lion-gryphon» from the Elizavetinski kurgan of the Kuban group, IV century B.C. forming a bronze cast ornament of horse-trappings occupies a special place as to style and treatment. [28] A part from the pose «ready for a leap», peculiar features are the fanged jaw and the treatment of the wing.

*

Unlike to the northern shores of the Black Sea, Western Asia and the Altai are rather rich in representations of winged lions. They are found in Middle Asia as well. Notwithstanding common features, we find diversity in the treatment and the style of rendering this fantastic animal.

The «winged lion» or more precisely the winged tiger — a wood-carved ornament of the horse-trappings from the Tuektin kurgan (fig. 4c) has the same shape of wing as that of the gryphon (fig. 4a) from the same kurgan. Its head is attached. We find characteristic features in the rendering of the hind paws with enormous claws, the same as for the tiger in scene of its combat with the wolf — the gold fastening of a garment from the Siberian collection (pl. IV, 1), and for the tiger of the Block sarcophagus from the second Bashadar kurgan (pl. IV, 2).

The winged lion from the first Pasirik kurgan — an application of polychrome felt on the saddle-cloth (fig. 5) — in the scene of the attack of this creature on a goat, has stylistically much in common with the representation of the one on another saddle-cloth from the second Pasirik kurgan. [29] It has an eared head with a small forelock, a low crest, and a fanged jaw. The wings twisted in a spiral are pointed forward. The tail has a traditional bird’s head instead of a tassel. The small strip representing the wooly lower part of the belly protrudes from under the wing. The croup has a traditional circle with a bracket.

The presence of horns on the head is the distinguishing feature of the winged lions from the second Pasirik kurgan in the scene of the attack of such a lion on an elk — a leather application on a veil (fig. 6a) — and of a horn-cut ornament of a torque (fig. 6c). On the leather application the horn is that of an ox, and on the horn-cut figure with an attached wooden head the

(108/109)

Fig. 3. (a) leather garment from second Pasirik kurgan; (b) gold placque from kurgan near Zourovka; (c) quiver from Karagodeushkh [Karagodeuashkh] kurgan.

(Îòêðûòü Fig. 3 â íîâîì îêíå)

Fig. 4. Wood ornaments from first Tuektin kurgan.

(Îòêðûòü Fig. 4 â íîâîì îêíå)

(109/110)

Fig. 5. Felt saddlecloth ornament from first Pasirik kurgan.

(Îòêðûòü Fig. 5 â íîâîì îêíå)

Fig. 7. Bronze clasp, collection of Peter the Great.

(Îòêðûòü Fig. 7 â íîâîì îêíå)

Fig. 6.

(a) Leather applique motif from second Pasirik kurgan; (b) gold phalera, collection of Peter the Great;

(c) torque ornament from second Pasirik kurgan.

(Îòêðûòü Fig. 6 â íîâîì îêíå)

Fig. 8.

(a) and (b) gold horse-trapping ornaments from Western Siberia;

(c) wood ornament from fourth Pasirik kurgan.

(Îòêðûòü Fig. 8 â íîâîì îêíå)

(110/111)

Fig. 9.

Gold boss, collection of Peter the Great.

(Îòêðûòü Fig. 9 â íîâîì îêíå)

Fig. 10.

(a) and (b) wolves of fig. 9 unfolded; (c) metal placque from Ordos

(Îòêðûòü Fig. 10 â íîâîì îêíå)

(111/112)

|

(112/113)

|

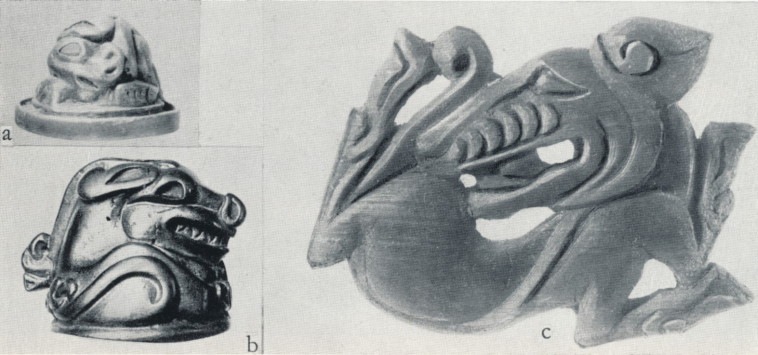

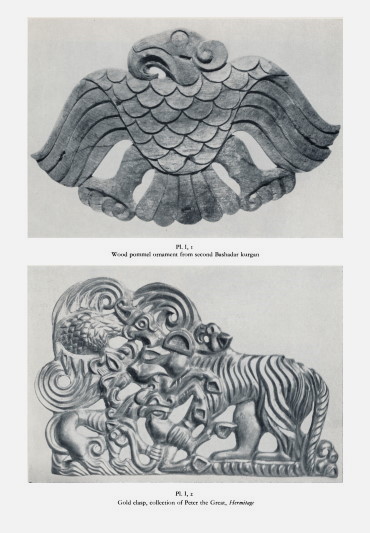

Pl. I, 1. Wood pommel ornament from second Bashadar kurgan.

Pl. I, 2. Gold clasp, collection of Peter the Great, Hermitage.

(Îòêðûòü Pl. 1 â íîâîì îêíå) |

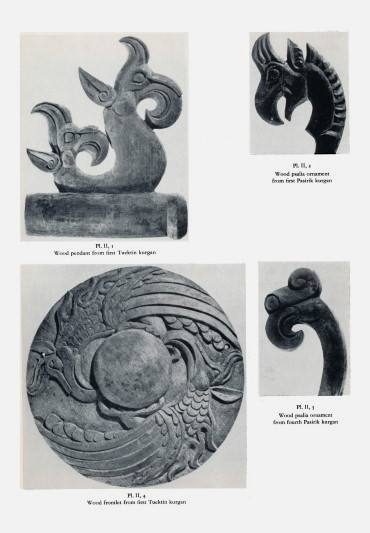

Pl. II, 1. Wood pendant from first Tuektin kurgan.

Pl. II, 2. Wood psalia ornament from first Pasirik kurgan.

Pl. II, 3. Wood psalia ornament from fourth Pasirik kurgan

Pl. II, 4. Wood frontlet from first Tuektin kurgan.

(Îòêðûòü Pl. 2 â íîâîì îêíå) |

(113/114)

|

(114/115)

|

Pl. III, 1. Bronze pole-top from Ulski kurgan.

Pl. III, 2. Bronze pole-top from Dnieper kurgan group.

Pl. III, 3. Ornament on sword sheath from Elizavetovski kurgan.

(Îòêðûòü Pl. 3 â íîâîì îêíå) |

Pl. IV, 1. Gold clasp, collection of Peter the Great, Hermitage.

Pl. IV, 2. Detail of sarcophagus, second Bashadar kurgan.

(Îòêðûòü Pl. 4 â íîâîì îêíå) |

(115/116)

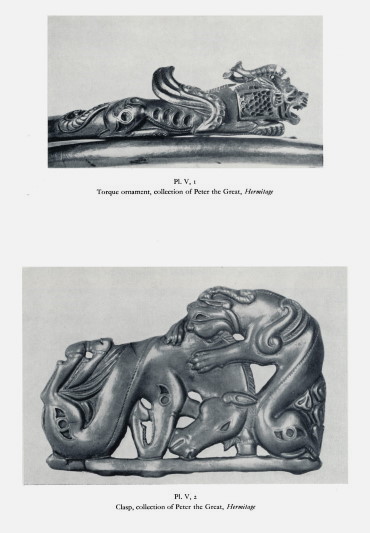

Pl. V, 1. Torque ornament, collection of Peter the Great, Hermitage.

Pl. V, 2. Clasp, collection of Peter the Great, Hermitage.

(Îòêðûòü Pl. 5 â íîâîì îêíå)

(116/117)

horns belong to a goat and terminate in pellets. These gryphons have similar, slightly lifted wings. Their tails terminate in a tassel.

The closest analogy to the winged lions of the torque from the second Pasirik kurgan is to be found in the gold ornament from the Treasure of the Oxus published by Dalton. This animal has the same long sharp ears, the horns terminating in pellets, the wings with the ends pointing forward.

On one of the gold plaques of the Treasure of the Oxus there is also a winged lion with the typical shape of the wing. The hind legs are those of a bird. [30]

Two pairs of winged lions are known to have come from Western Siberia: one pair ornaments a torque (pl. V, I), the other pair is found in the scene of a lion attacking a horse (pl. V, 2) which served as the fastening of a garment. The lions of the torques, with projecting forelegs and doubled-up hind-legs, seem to be crouching for a bound. They have half-open mouths with bared teeth and horns terminating in cups, very much like those of the gryphon of the gold armlet from the Treasure of the Oxus. The mane of the winged lion is represented by small scales partly covering one another, in the same manner as the plumage on the neck of the Amu-Daria gryphon. The shape of the wings is identical. The ribs on the body of the winged lion are marked by cells in the form of haricot beans. A circlet (point) between two triangles with concaved sides may be seen on the croup. The tip of the tail terminates in an eagle’s head, not in a tassel.

The scene of a homed winged lion attacking a horse (pl. V, 2) is remarkable from several view-points. First, attention should be paid to the twisted hind part of the body of the monster as well as to that of the horse, a manner of representing animals rarely met with among the Black Sea Scyths (e.g. the bronze-cast bridle-psaliae from the Seven Brothers kurgan) but widespread in the art of South Siberia, the Altai included. Secondly, the pellets at the tips of the horns and the tassel shaped as a leaflet on the tip of the tail — all these details found in representations of the winged lion from the Treasure of the Oxus are highly typical. [31] Finally, the presence of a circlet between two triangles on the croups of the monster and of the horse are the same as on the lion of the torque.

Thus the winged lions of the Siberian collection reproduced in pl. V, and the gryphons and winged lions of the Treasure of the Oxus belong to one and the same group of objects constituting the motives of the fine art of the Asiatic, or more precisely of the Sakian horse-breeding tribes. They may all be dated back to the V century B.C. for gryphons, and to the V-IV centuries B.C. for winged lions.

Generally speaking the motive of the gryphon was borrowed by the horse-breeding tribes from Assyria and Babylon, though some features characteristic of the gryphons reviewed by us, are peculiar to Persia. Winged lions with long sharp ears and the legs and the tail of an eagle were familiar to Babylon. In Assyria the head of a lion was sometimes replaced by that of an eagle having a crest. In Persia both varieties were used but with a new feature added to them — namely the horns. In some cases the short feathery tail of a bird was replaced by that of a scorpion. Among the Scytho-Sacian tribes both gryphons and winged lions had as a rule a lion’s body. Eagle-gryphons with the fore- and hind-legs of a bird may be met with only as an

(117/118)

exception. [32] The gryphons from Middle Asia and the Persia lion-gryphons have the hind-legs of a bird, e.g. those on the polychrome tiles in Susa. As we see horned lion-gryphons are found in Western Siberia (pl. V) and in the Altai as well as in Middle Asia.

Of exceptional interest is the bronze belt-clasp coated with a gold leaflet with a chased outer surface from the northern shores of the Black Sea, which is among the collections of the Hermitage (fig. 7). This clasp represents the scene of a «winged tiger» attacking a mighty fantastic beast having the body of a tiger or a lion, but supplied with horns. Special attention should be paid to the horns of this beast, shaped like those of a ram, similar to those of the lion-gryphon from Susa; also to the shape of the wing with curled-up ends, of the other beast, as well as to the presence of a «comma» on the shoulder and a «semi-colon» on the croup of both the beasts, the probable date of this clasp being the late centuries B.C.

Worth special consideration is the fact that the conventional signs serving to accentuate the details of the body not only of the gryphon but of other animals as well, were characteristic of the horse-breeding tribes, whereas they were lacking in the art of the tribes inhabiting the northern shores of the Black Sea.

On the Assyro-Babylonian representations of animals the muscles of the paws were usually accentuated by the figure of a horse-shoe with sharpened ends. These figures are found later among the objects of art in Near and Middle Asia. Figures of «apples and pears» according to the terminology introduced by A. Roes, [33] on the shoulder of an animal are characteristic of the Persian art of the early Achemenid epoch. These figures were represented on some objects of Persian art in the V century B.C. as well, but alongside of them there existed a point, a comma, a semi-horse-shoe and a bracket placed on the shoulder and on the croup of the animal. Such figures may be seen on the lion and on the lion-gryphon of the polychrome tiles in Susa. They are also known in the art of Middle Asia, e.g. on the gryphons of the gold armlet from the Treasure of the Oxus. The above-mentioned signs were extensively used in their art by the Altaian tribes, and were also met with in the art of the West Siberian tribes, e.g. on the croup of the elk attacked by a panther, from the Siberian collection (fig. 6b). On a number of objects of art which I am inclined to consider as belonging to a comparatively late epoch, e.g. the second half of the V or the first half of the IV centuries B.C., a point or a circle with a triangle was placed on the shoulder and a point between two triangles with concaved sides — on the croup of the animal. This detail is clearly seen on the picture of a winged lion on the torque, on the group of the winged lion attacking a horse (pl. V) and on the winged lion-gryphon from the Treasure of the Oxus. [34]

I should like to mention here that Rostovtzeff in one of his works depicts a gold armlet from Northern India belonging to the Peshawar Museum. [35] We see on it fighting lions or tigers with twisted bodies and the already familiar signs of a point or a circlet and a triangle with concave sides on the shoulder and on the croup of the beasts, with figures like the grains of haricot beans on the breast, similar to those of the lion-gryphon on the Siberian torque. It is highly probable that this armlet originates from Middle Asia. It must be remembered that the collec-

(118/119)

tion which we call the Treasure of the Oxus was acquired by Sir A.W. Franks in Peshawar, India, in 1880.

The origin of these details of treating animals by Near Eastern and Euroasiatic horse-breeding tribes at the epoch concerned is a problem which is still unsolved.

The fact is that in the art of the Scyths of the northern shores of the Black Sea, especially at an early epoch (the Ulski kurgan) we often see the head of an elk, or a griffin’s head on the shoulder of the animal. In the works of art of the Altaian tribes there exists a common device of accentuating the body by representing figures on it resembling a whorl or an “auroch’s horn” (fig. 6a), or a triangle with concave sides. These were later replaced by figures similar to a point, a comma, bracket or a haricot bean. Thus in the works of art of Upper Asia, in the abovementioned lions and lion-gryphons of Susa in particular, I am inclined to see the Persian art of the V century B.C. as influenced by the art of the horse-breeding tribes of the Asiatic steppes, but not vice versa.

I consider the conventional signs in the form of a circlet between two triangles, giving salience to the shape of the animal’s body, to have appeared in the art of the Euroasiatic horsebreeding tribes at a comparatively late epoch, for the reason that they became characteristic of the Sarmatian art.

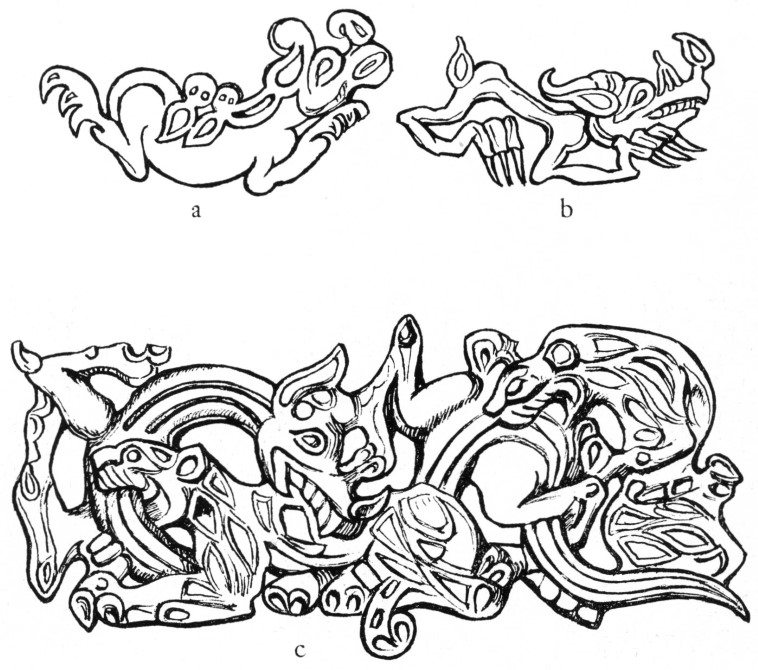

*

Wolves have always been a plague to the cattle-breeding peoples of the Euroasiatic steppes and forests and low hill-lands. As a result of the damage the wolves inflicted on the households and owing to the difficulties encountered in beating them off, supernatural strength was ascribed to these animals, fairy-tales and legends were told about them. Not only did they fight for their prey against such mighty beasts as tigers and griffins (pl. I, 2), but together with gryphons or by themselves (pl. IV, I) even ventured to attack the tiger.

Different representations of wolves are known in the Scythian art of the northern shores of the Black Sea, in the southern Urals, in Western Siberia and in the Altai. There is even a gold armlet with wolves pictured on it which comes from Middle Asia. [36]

There is much diversity in representing wolves. Various are the poses given to the wolves, poses often stipulated by the shape of the object in which or on which the wolves were represented. At the same time there existed common features characteristic of all or almost all the representations of wolves in the art of the Euroasiatic horse-breeding tribes.

A head of disproportionate size often equalling a third or even a half of the body of the beast is to be mentioned first. The small wood- carved figure of a wolf- the ornament of horsetrappings from the fourth Pasirik kurgan serves as example of this (fig. 8c). Besides the enormous head with the twisted upper lip, the dislocated hind part of the body with a stripe along the spinal column, and the soft paws are worth mentioning. Of great interest is a similar representation of a «winged» wolf with a large head and bared fangs — a gold plaque from the Kuban region, dating to judge by its style, from the late centuries B.C. [37]

A turned-up nose with a small eagle’s head often placed on its tip, is the second characteristic feature in the treatment of the wolf’s head with bared fangs and twisted upper lip.

(119/120)

In one of his works Rostovtzeff mentions that representations of wolves with turned-up nose tips may be found in the late Babylonian and Assyrian art. [38] I am not familiar with such interpretations but beyond doubt they are highly characteristic of the art of the Euroasiatic horse-breeding tribes.

One should distinguish between realistic and “mythological” representations of wolves, the latter being especially numerous in Western Siberia. The presence of a mane composed of small eagle’s heads along the neck (pl. IV, 1) and of a small eagle’s head at the tip of the tail is characteristic of these representations. The latter detail may be detected on the fantastic animal tatooing of the chief of a tribe from the second Pasirik kurgan, one of which is presented in fig. 2. This kind of rendering is helpful in dating a number of objects belonging to the Siberian collection of Peter the Great. The second detail very important for the same purpose is the manner of rendering the striped skin of the tiger with the help of zigzag lines, and of the long clawed paws — a manner identical with the representation of tigers on the Block sarcophagus and on its lid from the second Bashadar kurgan (pl. IV, 2) and with the rendering of the tigers of the Siberian collection (pl. I, 2; pl. IV, 1).

Up to now we have spoken almost exclusively of the art of the horse-breeding tribes which inhabited the present territories of the USSR. In referring to the works of art of the Mongolian tribes and to those of the tribes of Northern China belonging to the same epoch it is worth mentioning that there are hardly any dated objects among them found during excavation-work carried out for scientific purposes. Thus we may judge of the casual finds in this vast area only by their motives and style.

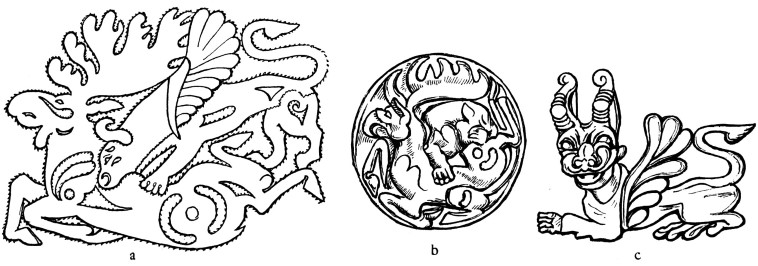

It should be noted that among several thousand of works of art of the Mongolian and North Chinese tribes, mostly bronze cast ornaments (so-called Ordos bronzes), there is not a single representation of an gryphon or a winged lion. Those fantastic animals of Upper Asia evidently did not penetrate eastwards beyond the Altai.

There are on the other hand, not a few renderings of mythological eagles in the interpretation characteristic of Western Siberia there, the birds being most often represented in scenes of combats. [39]

Numerous are the representations of small eagle’s heads with forelocks treated in a realistic manner as in the Altai, in addition to those treated conventionally as in the art of the western horse-breeding tribes. [40] Such small heads served for ornamenting different objects, handles of daggers in particular. [41] They were sometimes placed on the tip of the tail and of the horns of different animals.

Special attention is attracted by the treatment of wolves which is similar to that of West Asia and the Altai. Small figures of wolves couchant — a gold ornament of horse-trappings from Western Siberia — are shown in fig. 8a, b. Similar representations are to be found among the Ordos bronzes. [42]

In the Siberian collection there are gold hemi-spherical ornaments with carnelian inlaid in the centre (fig. 9) — the ornament of a garment. Mythological wolves with inlaid bronze are

(120/121)

placed along the circumference of this ornament. Fig. 10a, b present those ornaments as unfolded. Similar pictures of mythological wolves are also to be found in the Ordos samples. [43]

In connection with representations of wolves in the art of the Euroasiatic horse-breeding tribes there arises a question which I should like to dwell on more circumstantially.

In the Siberian collection we see gold fastenings of garments and belt-clasps with representations of serpents. [44] Serpents are found among the Ordos bronze ornaments as well, there being among them a metal plaque (fig. 10c) published by A. Salmony which is of special interest. [45] We see on it a lizard or serpent with a wolf’s head, attacked by two tigers. The rendering of the striped skin of the tiger differs from that of the Siberian and Altaian tigers, but is close to the latter. The head is typically wolfish with the up-turned tip of the nose. The exact date of this metal plaque is unknown but I believe it might belong to the late centuries B.C.

The representation of a wolf with the body of a serpent, or that of a lizard is undoubtedly the result of the creative fancy of the cattle-breeding tribes of the prairies, and the question arises whether these representations might not have served as prototypes to the Chinese dragon. Contrary to India, there was no official worship of the serpent in China. Popular traditions, legends and fairy-tales where serpent-dragons should figure are scarce in China. Nevertheless there exist prejudices and rites connected with the serpent, as well as the belief that serpents have paws though they are concealed. Alongside with this the dragon as one of the characteristic motives occupies a stable place in Chinese fine art. The origin of the dragon presents a special problem and I do not attempt to solve it here. I should only like to emphasize the fact that the art of the horse-breeding tribes is not to be overlooked when solving the problem of the dragon’s appearance in Chinese art.

In comparing the works of art of West Siberian and Altaian tribes with those of their eastern horse-breeding neighbours it becomes clear that beyond doubt the artistic value of the former is higher. In the works of art of the West Siberian and Altaian tribes one may find an analogy with the majority of the different bronze objects of the eastern tribes. Copper cast works of art of the Mongolian and North Chinese horse-breeding tribes are, with rare exceptions, imitations of more perfect the Western models. The same should be said of scenes of the combat of a tiger and a yak embroidered on the far-famed felt carpets from the sixth Noin-Ulin kurgan in Mongolia and the attack of an eared eagle on an elk. [46] The famous monster-eagles of the combats from the Siberian collection served as prototype to the one from the Noin-Ulin kurgan, and the tigers of the same collection were prototypes of the Noin-Ulin tiger. However it should be mentioned that unlike the very expressive and dynamic Altaian scenes of wild beasts attacking cloven-hoofed animals, the scene of the combat between the yak and the tiger is static. This is true in particular of the tiger’s pose.

If we did not limit ourselves to the above-treated motives of the art of the Euroasiatic nomads but considered all the motives of their fine arts, we might draw the conclusion that the so-called Scythian Animal Style of art prevailed over all the area inhabited by the horse-breeding tribes, from the Carpathian mountains in the West to the Altai, the T’ien Shan and the

(121/122)

Pamirs in the east. This community of style which found expression in a peculiar manner of depicting animals is the result of the ethnical kinship of those tribes as well as of their intertribal relations. Early samples from the northern shores of the Black Sea (the Litoj and the Kelermes kurgans) clearly reflect the influence of Assyrian art on that of the Scyths. In the later samples the influence of Grecian art may be traced. Asiatic Sakian tribes, the Altaian included, evidently experienced the influence of the Near Eastern art, in its Persian variety in particular. Representations of gryphons serve as convincing evidence of this. The peculiar art of the Scytho-Sakian tribes with its Animal Style has to some degree influenced the art of the Minousinsk region. In the late centuries B.C. the fine art of the eastern horse-breeding tribes, the Hsiung-nü in particular, represented by the Ordos bronzes was subjected to the same influence. The development of the Hsiung-nü art was at first independent and only at later stages grew to be influenced by Chinese art. But this forms a special subject covering a wider range than the questions touched upon in this paper.

[1] Iranians and Greeks in South Russia, 1922; The Animal Style in South Russia and China, 1929.

[3] Scythian Art, 1928.

[4] The Art of the Northern Nomads, 1942.

[5] “Sarmatian Gold Collected by Peter the Great”, Gazette des beaux arts, 1947-1950.

[6] The Treasure of the Oxus, 1905 (first ed.); 1926 (2nd. ed., including “other examples of early Oriental metalwork”).

[7] “Hunting Magic in the Animal Style”, Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, Stockholm, 1932.

[8] Sino-Siberian Art in the Collection of C.T. Loo, 1933.

[9] A start has been made through the publication of A. Godard’s Le trésor de Ziwiye, 1950.

[10] Minns, Scythians and Greeks, 1913, fig. 192.

[11] Dalton, 1926, pl. xi, no. 25.

[12] These two kurgan sites in the Ursul river basin of the Central Altai were excavated in 1954 (Tuektin) and 1955 (Bashadar). The excavation results are to be published in the near future in my work, The Culture of the Central Altai Populations in Scythian Times [1960].

[13] Minns, 1913, fig. 69.

[14] Roes, «Achaemenid Influence upon Egyptian and Nomad Art», Artibus Asiae, 1952, xv, 1-2, p. 18, fig. 2.

[15] The great Pasirik kurgans were dated by me in the V century B.C. by analogy with contemporary Scythian kurgans elsewhere and by the presence, in kurgan 5 at Pasirik, of Near Eastern tissues and carpets from that century. The differences in date among the Pasirik kurgan group were established by counting the annual rings of the logs used in their construction.

[16] Minns, 1913, fig. 183.

[17] Borovka, pls. 5A and 5B respectively.

[18] Minns, 1913, fig. 193.

[19] Rostovtzeff, 1922, pl. VI.

[21] Minns, 1913, fig. 196.

[22] Rudenko, 1953, fig. 163 and pls. cix, 2 and cxi.

[23] Dalton, 1926, pl. I, no. 116.

[24] Rudenko, op.cit., pl. cxi.

[25] Dalton, 1905, pp. 109-110.

[26] M. Dieulafoy, L’acropole de Suse d’après les fouilles exécutées en 1884, 1885, 1886, sous les auspices du Musée du Louvre, 1892, pl. ix.

[27] Minns, 1913, p. 208, fig. 27.

[28] Rostovtzeff, 1929, pl. xi, fig. 1.

[29] Rudenko, 1953, pl. cix, fig. 2.

[30] Dalton, 1926, fig. 50, no. 23; 1905, pl. xii, no. 28.

[31] Dalton, 1926, fig. 46, no. 23.

[32] Rudenko, 1953, figs. 75, 163.

[34] Dalton, 1926, fig. 5o, no. 4.

[35] 1929, pl. xviii, fig. 5.

[36] Dalton, 1926, pl. xx, no. 144.

[37] Minns, 1913, fig. 205.

[38] 1929, note on p. 12.

[39] Op.cit., pl. xxvi, 1, 2; Andersson, op.cit., pls. xxxii, 1, and xxxiii, 1; Salmony, 1933, pl. xxii, 1.

[40] Salmony, ibid., pl. xvii, 1, 4, 5; Andersson, pl. xxv, 10; xxvii, 4-7.

[41] Ibid., pl. viii, fig. 25.

[42] Rostovtzeff, 1929, pl. xxviii, 2; Salmony, 1933, pl. x, figs. 3, 4.

[43] Rostovtzeff, 1929, pl. xxviii, 2; Salmony, 1933, pl. x, 3.

[44] Minns, 1913, figs. 193, 195, 200.

[45] Op.cit., pl. xxii, 3.

|

S.J. Rudenko

S.J. Rudenko