G.I. Borovka

G.I. Borovka

Scythian Art.

// London: Ernest Benn, Ltd. 1928. 111 pp., 74 pl.

Scythian Art.

[ńŽˇ ůšÓŠŮÚ‚ŗ ‚ ÚŚÍŮÚ ÍÓŚ-„šŚ šÓŠŗ‚ŽŚŪŻ ŤŽŽĢŮÚūŗŲŤŤ,

ÍŗÍ ŗ‚ÚÓūŮÍŤŚ ÚŗŠŽŤŲŻ (Ůž. ŮÔŤŮÓÍ), ÚŗÍ Ť šÓÔÓŽŪŤÚŚŽŁŪŻŚ.]

The centuries preceding and following the year 1000 b.c. were a veritable age of national migration. About that time the invasion of the west Indo-European tribes, of the Greeks and the Italici, and the advance of the east Indo-European Medes and Persians finally shattered the great pre-classical civilizations. Approximately at the same epoch the whole vast ocean of peoples, grouped together by the Greeks under the collective name of Scyths, was set in violent motion. Of the causes of these mighty popular movements in the vast steppe region north of the Caucasus and Iran we know practically nothing. The history of those regions in pre-classical times is almost a sealed book. Even for the classical epoch our sources of information are exiguous and the archaeological record is still inadequately studied; before we can interpret it, the material must be comprehended in its inner significance. We can only suggest hypothetically that all these popular movements, the western and the eastern alike, were interrelated and are to be regarded as a single great phenomenon.

Still one ultimate result of this migration of ďScythianĒ tribes does come fully within our ken. The westernmost of these peoples, the Scyths proper, took permanent possession of the steppe region of South Russia and entered into close relation with the classical world on the coasts of the Black Sea. From this contact between two worlds, which as we shall see were quite heterogeneous, arose most significant and enduring results.

The first and principal consequence of their interrelation was the incorporation of the whole Scythian region north of the Caucasus and the Black Sea in the living body of the ancient world. From the annihilation of the civilizations of the ancient East through waves of fresh peoples to the repetition of the same process at the end of the classical age, the course of evolution

(15/16)

in Scythia was, despite all local peculiarities, the same as in the other frontier provinces of the Greco-Roman world. The cultural foundation created by the classical civilization in regions such as Gaul or Scythia is the basis on which modern life has been built up, in Russia as much as in the West.

But the effects of Scythiaís intercourse with the classical world were still more far-reaching; they spread to the east across the Ural to the Altai and even right into Mongolia. We encounter them as fundamental elements in the art of ancient China in pre-Christian times and their echoes are still vibrating to-day throughout the Far East.

How did this contact between classical culture and the unknown and mysterious world of the East come about?

Its scene is a land of ancient culture. Unfortunately the investigation of the antiquities which the soil has richly yielded us is still very incomplete. Only a few stages of the evolution stand out distinctly. The whole western part of the South Russian steppe land up to the Dniepr valley was occupied at the end of the Stone Age by an advanced culture created by a sedentary population living by agriculture and pasturage. It is termed the Tripolye culture and is celebrated for its splendid pottery, brilliantly decorated with painted designs. It belongs to the same cultural group as the so-called spiral-maeander pottery which extends throughout the Danube valley and the Balkans, and its orientation is markedly western. It is to be noticed that this region exhibits relations with the west also in Scythian times.

In the early Copper and Bronze Ages we meet a culture rich in gold in the Kuban district north of the Caucasus which is most brilliantly illustrated by the Maikop grave. Massive gold and silver models of oxen, a multitude of stamped gold plaques,

(16/17)

necklaces of gold, silver and carnelian beads, seventeen gold and silver vases, two of them engraved with pictorial scenes ó such are the treasures that make this grave a unique phenomenon, and reveal the high level of civilization reached in this region even at so remote a date. Professor Rostovtseff has shown that we have here to do with the same culture which, extending over a wide area to the east, meets us in the oldest deposits in Mesopotamia and pre-dynastic Egypt. Other finds are connected with those from Maikop and show that this culture was widely spread and well represented in the Kuban district. The complete divergence of the funeral furniture and the forms of tools and weapons from all European types shows that here, in contrast to the Tripolye culture, we are dealing with an independent eastern aspect of civilization. It seems that this culture aroused a very permanent influence on wide regions in Russia right into the full Bronze Age.

Another funerary deposit of the Kuban district ó from Ulski Aul ó dating from the Bronze Age, shows somewhat divergent characteristics which point to a relation with Aegean culture. It included primitive female statuettes of alabaster, corresponding to the well-known specimens found in great numbers on the Cyclades. Further points of contact between these two areas of civilization can apparently be detected.

On the other hand, other signs suggest that in the full Bronze Age, South Russia was exposed to strong influences emanating from Asia Minor and the Caucasus. The whole Copper and Bronze Age of South Russia is distinguished by extremely numerous but generally very poor graves containing contracted skeletons, often showing traces of red colorization, which probably cover a very long period of time. Several groups can be distinguished with the aid of the form of the tombs, and the

(17/18)

character of the pottery they contain. The meagre cultural picture afforded by the graves can, however, to some extent, be supplemented by chance deposits and isolated finds. In the western part of what afterwards became known as Scythia, an influence from the Donau region is clearly discernible in the late Bronze Age, and thus the steppes are once more brought into the sphere of Central European pre-history. It has even been suggested that the whole steppe region that stretches along the north bank of the Black Sea was, at the beginning of the Metal Age, flooded by a great stream of culture, originating in Northern Europe. But our picture of the sequence of cultures remains fragmentary and misty. We can only say that even in these early times the region reveals a many-sided historical life which came into contact with the advanced centres of civilization in the ancient East and the Aegean. If the course of development in this remote provincial region was relatively independent, still the picture presented by this early epoch already resembles that offered by later times.

It may be assumed with the highest degree of probability that all these cultures did not vanish without leaving a trace, nor simply succeed one another without intermingling. It is more likely that one culture overlaid the other and that survivors of the earlier population remained in their former haunts even when the region was repeatedly occupied by fresh intruders. That can be asserted with certainty of the last forerunners of the Scyths, the Cimmerians. The remnants of this people were evidently concentrated on both sides of the Straits of Kerch, between the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, on the eastern promontories of the Crimea and on the islands off the Kuban delta, forming the present Tamen peninsula. Their presence on those shores is attested by the ancient place-names, above all by the name of

(18/19)

the Straits themselves, which were called by the Greeks the Cimmerian Bosporus.

Of the Cimmerians we know little more than that they were driven from South Russia by the Scyths. Some of them combined with their assailants in the VIIIth and VIIth centuries to constitute one of those waves of invaders which occasioned the final collapse of the civilizations of the ancient East. They fell upon Asia Minor and spread terror and destruction over the realms of the Chaldæans in Van (Armenia) and of the Lydians and Phrygians in Anatolia and even over the New Assyrian Empire. Greek and Assyrian sources give a concordant account of these events.

This first onslaught of Scythian tribes, partly on the trail of the Cimmerians and partly in alliance with them, is of importance in so far as it brought the world of peoples living and wandering north of the Caucasus and Iran into touch with the life of Iran and Hither Asia. A section of the Scythian tribes actually settled down in the Armenian regions and no doubt thereby again strengthened the relations which must long have subsisted between the northern and southern shores of the Black Sea. At the time of the expansion of the Persian Empire a couple of centuries later, the Scyths who lived round the Caspian Sea and to the east thereof, came into contact with the Iranian world. It is probable that the strong Iranian influences which made themselves felt even in South Russia and at the same time spread far to the east radiated from these regions.

At the time of the Cimmerian invasion of Asia Minor the flood of Scythian tribes was spreading all across the South Russian steppes from the Urals to the Caucasus on the south and to the Balkans on the west. To the Greeks they always appeared as nomads, and the Greek authors never tire of

(19/20)

describing Scythian manners and customs. Their accounts agree in many points with what we know of the warlike nomads who, to-day, pasture their herds of cattle and horses on the Caspian and Central Asian steppes. The breeding of cattle and horses was favoured by the conditions of their new home and remained one of the foundations of the Scythsí prosperity down to their last days. But Herodotus also mentions the Scythian tribes of the agriculturalists (Georgoi) and the ploughmen (Aroteres) and on the middle Dniepr, and in part of the Kuban district we find clear traces of a sedentary population. Moreover, during the whole of the Classical Age, as much as to-day, corn was intensively cultivated on the black-earth country and formed the second chief factor in its highly developed economic life. The third element was provided by the fisheries on the great rivers and along the coasts. In addition the trade in furs and skins with the forest regions to the north and east, deserves mention. Finally, the gold of the Urals and the Altai began to flow westward in a rich stream through the agency of the Scyths.

The population must have been as varied in its components as in its occupations. Remains of the older peoples of the land must everywhere have survived and mingled with the Scyths. The clearest traces of them are found on the middle Dniepr. No doubt a strong Iranian element entered into the population of South Russia in Scythian times. Still signs seem to be multiplying that other ethnic constituents were also represented among them.

The whole population was divided into tribes governed by princes and grouped together under the overlordship of kings. The political organization was already firmly established by the VIth century, and the Scyths were able successfully to resist the attack of Darius of Persia. The typical graves of Scythian

(20/21)

princes from that period give an impression in close agreement with Herodotusí account of the burial rites of the Scythian kings and vividly reflect their wealth and their habits. The horse offerings are innumerable ó in one grave alone more than three hundred and sixty horsesí skeletons were found ó and the wealth of the Scythian graves in gold is inexhaustible. Weapons and vessels, horse-trappings and personal costume were all either made of solid gold or spangled with gold plaques.

But all these articles reveal most plainly the intensive Greek influence to which the Scythsí culture was exposed from its beginnings. Already in the VIIIth century b.c. a branch of the stream of Greek colonization had begun to pour into the Black Sea. That colonizing movement, starting from the coasts of Asia Minor, had cast the far-flung net of Greek City-States over the whole Mediterranean basin to Sicily and Gaul, and thus paved the way for the Hellenization of the ancient world. The same significance attaches to the foundation of Greek cities on the Black Sea coasts. From this time on the shores of the Euxine and its hinterland were inseparably bound up with the whole life of the classical nations and were incorporated in the ancient world as an integral part thereof. The fortunes of the Greco-Roman world were also the fortunes of the Pontic region. Ionians from the cities of Teos, Mytilene and Klazomenae on the north coast of Asia Minor were the first settlers; the Milesians followed them, and later, won the supremacy. So the young urban life that had arisen from the ruins of the old Ægean civilization upon a soil that had now become Greek was early transplanted to the Pontus. The magnet that attracted the Greeks thither was in the first place the inexhaustible multitudes of fish swarming in the great river estuaries with their lagoons and salt deposits. In addition, the export of grain and cattle

(21/22)

quickly acquired supreme importance. Scythia became one of the chief sources of supplies for the Greek world, the soil of which could no longer feed the ever growing population.

The earliest and most important Greek settlements in the Pontus were concentrated in just that territory round the Cimmerian Bosporus where the remnants of the pre-Scythian population had been penned up. Here first Phanagoria on an island in the Kuban delta and then Panticapaeum on the site of the modern Kerch on the shores of the Crimea played the leading part. In the west of the Pontus, Olbia, at the joint mouth of the Bug and the Dniepr, became the foremost city. From the moment of their foundation the Greek cities began a lively interchange, both of commodities and ideas, with the native tribes. We can watch Greek influence spreading with the victorious vigour of youth. Greek products, notably painted vases, were already to be found as far away as the Governments of Podolia and Kiev, and the heart of the Kuban district by the VIIth century. The country round the Cimmerian Bosporus became saturated with Greek urban civilization. It may be guessed that older elements of culture preserved here by the Cimmerians who were probably closely akin to the Thracians made this soil peculiarly responsive to such Hellenization. In any case, a strongly organized State arose here in the Vth century. Under the rule of a dynasty with half Greek and half Thracian names it embraced the surrounding regions and the Greek cities in a political unity, the Bosporan Kingdom. The archons of Panticapæum, the capital of the realm, style themselves kings in dealing with the native tribes and thus embody in their double title the double aspect of their power while preserving in contact with their Hellenic subjects the appearance of the free constitution of a City-State. The Bosporan Kingdom remained at all

(22/23)

times the cultural centre of the whole country on the north coast of the Pontus. Its wealth depended on the Greek citiesí flourishing trade in the natural resources of the land. Its prosperity was substantially increased when the colony of Tanaïs at the mouth of the Don, the terminus of the trade routes from the East, Central Asia and the Volga region became subject to it. From this moment Greek influence expands in manifold forms over all Scythia. The Scythian graves show how thousands of articles in daily use among the Scyths were manufactured by Greek artisans in the coastal towns. The Scythian chiefs possessed many marvellous jewels, the finest masterpieces of the Hellenic goldsmiths that we know.

But soon the reaction began. The native population was not content merely to absorb Greek influence, and to be enriched by the inspiration of Greek culture it began itself to reinforce and interpenetrate the citizen body in the Greek colonies. This reaction was slowly preparing in the course of centuries and came to the surface in Hellenistic times when, after the exhausting Peloponnesian War, the Greek settlements on the Pontus ceased to receive a continuous influx of new colonists from the mother land. From that time opens an age of trouble for the Greek cities. The native folk, themselves once more disturbed by Thracian, Celtic and Germanic wanderers from the west and fresh invaders from the east, begin to press upon the cities. The undefended town of Olbia on the west was the worst sufferer, till at length she was sacked by the Getx in the Ist century b.c. She only revived again slowly and on a smaller scale under the Romans. By the IInd century b.c., it was no longer the Scyths, but their eastern kinsmen, the Sarmatians, who were in possession of the open steppe. The Scyths, like the Cimmerians before them, had sought refuge in the Crimea, and there formed

(23/24)

a new State in the interior of the peninsula, a source of peril to the Bosporan Kingdom and still more to the town of Chersonnese.

These were disturbed, restless and perilous times, interrupted only by brief intervals of respite in which prosperity and civilization always blossomed forth afresh with astonishing vigour. Mithradates Eupator, king of the realms of Pontus, in Asia Minor, intervened in the contest with the Crimean Scyths. The Bosporan Kingdom became dependent upon him and he founded a new dynasty there. The years of his rule, the last decade of the IInd and the first half of the Ist century b.c., saw the northern coast of the Pontus directly involved in the world-shattering war which this prince waged against Rome. His masterful personality embodies the last revolt of the old native elements in the east against the victorious progress of Hellenic culture as the champion whereof Rome now girt up the iron strength of her organization for war. At bottom, it was the same process as we have been watching in Scythia. That is why, brief though the dependence of the Bosporan Kingdom on the Anatolian dynasty was, Mithradatesí rule left a deep mark on the Cimmerian Bosporus. The old political organization under which the Greeks enjoyed at least equality of rights and that not only at law, was broken down. The new State which took its place was a semi-barbarized society in which the native elements, now predominantly Sarmatian, took the lead. At the same time it, like the whole eastern portion of the ancient world, was politically dependent upon Rome, who assisted the Bosporan Kingdom and the other Greek cities on the north coasts of the Pontus against the restless and dangerous tribes of the steppe in order thus better to defend her own frontiers against barbarian inroads. But the pressure of the new peoples soon became too strong; Rome was too deeply preoccupied with her

(24/25)

own concerns, and in the IVth century a.d. the Bosporan Kingdom ceased to exist. First the Goths from the west, and then the Huns from the east overran the steppes and, save in Christian Chersonnese, put an end to classical life in these regions, the Huns being the principal agents of destruction. This is one scene from the first act of the Collapse of the Ancient World.

Such in brief is the story of Scythiaís fortunes. But what do we know of the Scyths themselves?

We possess no remains of Scythian literature. A written tradition emanating directly from the Scyths is altogether wanting. Only in the Greek authors, especially Herodotus, do we find full accounts of this people. But the Greek sources are reliable only in those sections which describe the life of their own kinsmen on the Pontus and the fortunes of the Bosporan Kingdom. The account of the true Scyths, the inhabitants of the vast hinterland, is for the most part confused and interwoven with legend and myth. Scythia seemed to the Greeks a strange and savage land, full of astonishing marvels lying somewhere on the far edge of the known world much as the Far East appeared to the eyes of Europeans as late as last century. It is certain that the Greeks dwelling on the Pontus possessed an accurate and thorough knowledge of conditions and events in the hinterland, and a sediment of such knowledge was no doubt carried by the stream of local historical tradition. But unhappily it has not survived to our day but has been almost completely lost. What we find in the remaining authors is usually, as in Herodotus, tales about strange customs and fragments from popular tradition, myths and ritual, repeated with childish wonder. Little is to be gleaned from such reports. In the first place, they seldom reach us first hand; only once or twice do they reproduce the writerís own experiences and views. Moreover,

(25/26)

the Greeks drew no distinction between the several diverse elements in the population, so that we cannot decide to which of them this or that trait should be ascribed. Finally, these reports are either relatively colourless or obviously tinged with mythology.

What we learn of the customs and manners of the Scyths forms a picture which would be equally typical of any nomadic people. The women and children live in wagons provided with roofs; the food, consisting principally of meat and maresí milk, is cooked at the open fire; near by, graze the herds of horses, cattle and sheep, and the whole band wanders slowly from place to place. By night the men come into camp; during the day they ride away on their steeds to hunt on the open steppe or travel for longer periods on warlike expeditions. Obviously such accounts can only refer to the nomadic tribes, but it remains questionable whether the true Scyths themselves actually were such. Dress is suited to the cold winter climate of these regions. Men wear trousers and a double-breasted sleeved jacket, fastened with a girdle. The head is covered with a peaked cap, provided with two flaps coming down over the ears, and the feet are protected by supple leather boots. The chief weapon is the bow and arrow, both carried in a case, the gorytus, at the side. But lances and a sword, usually short, are also in use.

The Greek authors have much to say of the Scythsí love of war and of their many cruel customs. He wins honour who slays a foe; drinking vessels are made from the skulls of slain enemies; the blood from the foemanís death wound is drunk; his skin is used to deck weapons and harness. One tribe bears the name of Androphagoi, i.e. cannibals. The burial rites are bloody too. A great manís wife follows her lord to death

(26/27)

and is buried with him. In honour of princes and kings many of their subjects are sent to the underworld. All that he used in this life as weapons, clothing and ornaments, are laid beside the dead man in his grave. Numerous horses are included in the wealth which he takes with him. Horses are also offered to the gods, especially the war god. The latter also receives human sacrifices, and is worshipped under the guise of a sword. The supreme deity is female; her cult is entrusted to the queens. The Enarees (impotent men) also worship the same goddess. A male deity who had intercourse with the supreme goddess is represented as the ancestor of the Scyths; his native name was kept secret but Greek tradition calls him Herakles. The recurrent stories of the Amazons also deserve mention: they had waged war upon the Scyths and Cimmerians and had made alliance with them. Such tales are evidently inspired by reminiscences or survivals of matriarchal organization.

No distinct picture results from all these reports. Even when they are supplemented by linguistic researches into geographical, divine and personal names and by representations of scenes from Scythian life, this picture remains blurred. It is clear that many of its details, especially in later days, are to be referred to an Iranian element. Beside them, constituents are present which are related to the old native world of the Caucasus and Asia Minor. On the other hand, statements are constantly repeated, emphasizing, apparently with justice, points of agreement with Finno-Ugrian or even Mongolian tribes.

One important point is still to be noted. In the enumeration of the nations and the account of the trade routes the great tradition takes us far into the north-east Russian forest country on the Volga and Kama on the one hand and on to the Transcaspian steppe right up to the Altai and the borders of China

(27/28)

on the other. Among the Budini, in the Kama district, which has been inhabited right down to our own days by Finnish tribes, they speak of urban settlements peopled by a mixed population of Greeks and barbarians. All such tribes seemed to the Greeks to be cast in one mould with the Scyths. The little that they tell us of their customs agrees with this and is in many respects confirmed and supplemented by the accounts given by early Chinese authors of the Middle Kingdomís northern neighbours.

However, literary sources are not the only ones available. Through the excavation of Scythian burial places, a rich archaeological material has been exhumed by Russian scientists and amateurs especially since the middle of last century. Much, very much, alas, has been sacrificed to the lust for gold that such rich graves could easily gratify. Nevertheless, the Hermitage, where the mass of the finds has been concentrated, and many museums in Moscow, Kiev, Ekaterinoslav and other cities possess incredibly rich collections of antiquities from the Scythian period. It is the conspicuous merit of Prof. Rostovtseff that he has taught us to bring an unprejudiced mind to the study of these remains of a strange culture in their full individuality. They speak to us in unmistakable language, and in their enormous wealth in gold and their peculiar character, a blend of native, Oriental and Greek elements, they reveal the high standard and striking individuality of Scythian civilization. But, what is yet more important, these finds provide us with a direct, unadulterated and authentic source for the study of the dumb Scythian world. With the aid of this material we are enabled clearly to recognize the diverse foreign influences to which Scythian culture had been exposed. We can distinguish the Greek and Iranian elements, the impulses emanating from the

(28/29)

Caucasus and Asia Minor and also from western Europe. We find that, despite the intensity of the Greek influence in particular, an independent native element, strong and indeed dominating, had been at work. Here, for the first time, we can grasp it in its unsullied purity and completeness.

The first point that strikes us is the wealth of Scythian culture in gold. Never before or since, apparently not even in the days of the Maikop civilization, was gold in such universal use in this region. And scarcely any other culture, not even ďMycenæ rich in gold,Ē can rival Scythia for its superfluity of gold. Siberia is the sole exception. To-day, indeed, finds of gold in Siberia are extremely rare. But we possess ancient reports speaking of the fabulous wealth of the graves of the Siberian steppe. The Russian immigrants, especially in the XVIIIth century, have systematically plundered these graves and melted down the gold and silver they found, and now hardly a grave is left in which we can hope to find gold objects. For the preservation of the unique collection of Siberian goldwork in the Hermitage, we have to thank the personal intervention of Peter the Great, who issued an ordinance that such finds must not be melted down but surrendered to the ďArt RoomĒ at St.Petersburg. Unhappily, this command was soon forgotten. Nevertheless, the objects, striking for their solidity and their lavishness in material wealth, prove that Siberia must have excelled even Scythia in its wealth of gold. None the less, the use of gold among the Scythians had assumed extraordinary proportions, even when measured by modern standards. It implies that the Scyths controlled a regular and perfectly secure traffic with the goldfields whence the metal was won, that is, with the Urals and still more with the Altai.

The individuality of the Scythian culture stands out very

(29/30)

distinctly in the funeral structures in which the numerous horses buried with the departed play so prominent a part. The graves of the archaic epoch from the Kuban district are especially characteristic; in them the horses originally encircled the tentshaped wooden tomb on all four sides. This, too, is a feature which appears first with the Scyths and then vanishes and is nowhere else exactly paralleled.

But the specifically Scythian element expressed itself most definitely in the distinctive artistic style that the Scyths brought with them. This style is thoroughly individual, so individual that it long remained quite unintelligible; only in recent years have we begun to understand it. This style is at once so lively that a modern eye is instantly caught by it, and so fanciful that the observer at first can scarcely make out the details of the presentation. It produces the effect of an impressionistic ornamentation, but its components are living bodies. The artistic power of the style is very great, yet all its products are infected with a touch of the primitive.

None of the cultures with which the Scyths came in contact on their westward advance possessed anything comparable. In the interior of Europe, in Greece, in Asia Minor, in Mesopotamia and in Persia a totally different style of art was current. On the other hand, a thoroughly analogous style ruled in the eastern countries bordering upon Scythia from the Caspian to beyond Lake Baikal. Of course we can distinguish everywhere local varieties. Scythia, Permia and Central Siberia, the three chief centres, each exhibits its own peculiarities. But taken together they constitute an unitary stylistic group contrasted with all other known cultures.

The style ruling in these regions is very rightly called an animal style. Its motives are composed of the bodies of animals

(30/31)

ó now complete animal forms, now individual members, espech ally heads or legs. The several motives are decoratively combined and blended together in the most fantastic manner. The products are the most weird and puzzling shapes, especially when we reach forms already in process of degeneration. Sometimes the figure of a whole animal is covered with other complete or partial animal shapes. Sometimes we meet the converse, for instance, a birdís head decorated with animal shapes. The antlers of an animal of the deer tribe, used to fill up spaces, proved a very prolific motive. It gives birth to a whole series of variants in which the ends of the antlersí branches turn into animalsí or birdsí heads. An unfettered fancy is at play expressing itself in these protean combinations. The styleís ingenuity in creating ever fresh and unexpected shapes was inexhaustible. But innumerable as the variations are, they may for the most part be traced back to a few fundamental motives. Whether the design be executed in gold or silver, in bronze or iron, in wood or bone, or even in stone, as in some still rare cases, we generally meet the same motives constantly recurring in new combinations and stylizations.* [ŮŪÓŮÍŗ: In 1924/25, through the excavation of barrows in Mongolia, the Koslov expedition discovered the first examples of Scytho-Siberian art applied to textiles ó two carpets decorated with scenes of animals fighting.]

Among these motives that of a sitting animal of the deer species deserves to be mentioned first of all on account of its extraordinarily wide distribution. The most splendid example of the motive is the large representation of a sitting stag, hammered out of a solid gold plate found at Kostromskaya Stanitsa, in the Kuban district. The object evidently served as the emblematic decoration on the centre of an iron shield (Plate 1). [ŌūŤž. ŮŗťÚŗ: ő ŪŗÁŪŗųŚŪŤŤ ŠŽˇűŤ Ůž. ŮÚŗÚŁĢ ņ.ř. ņŽŚÍŮŚŚ‚ŗ.] The characteristic quality of this motive consists in the following

(31/32)

traits: The legs are doubled up under the body in a quite peculiar way so that the forelegs lie pressed against the body and the hind legs are extended forward below them. In this case the animal is depicted strictly in profile so that only one of each pair of legs is represented. Though this is a common, in fact the normal, form, it is not rigidly adhered to. A further characteristic of this motive is that the neck and head are stretched far forward as if in continuation of the lines of the body. The antlers accordingly lie extended along the back and relieve the flatness of the upper contour of the figure with their many spiral or hooked branches, the front pair of which project forward apart from the rest. This motive was often repeated with all its peculiarities. On each of the twenty-four rectangular fields on the chased gold plate decorating a gorytus (i.e. case for bow and arrows) from Kelermeskaya Stanitsa, also in the Kuban district, it recurs unchanged (Plate 2). The same motive often appears on little stamped gold plates for sewing on garments. These have been found in the Dniepr district and elsewhere as well as in the Kuban valley (Plate 3 E). Thus we are evidently dealing with a well-established type.

We can already observe in this first example the characteristic peculiarities of the Scythian artistic style. The portrayal is anything but naturalistic; on the contrary, the treatment is throughout markedly stylized, one might almost say, conventional. The motive itself, taken as a whole, is not true to life. It is not even clear what position the animal is conceived as occupying. We might hesitate to say whether we are looking at a leaping or a sitting beast. And what could be more conventional than the treatment of the antlers or the whole manner in which the legs are tucked up under the body, not to speak of the modelling of the body, breaking it up into large unitary

(32/33)

surfaces in an almost tectonic fashion! And yet what fresh and original liveliness is expressed in this representation! How perfectly the artist has caught and reproduced the essential peculiarities of the stag in the pose of head and neck! The delicacy and elasticity of the body, the grace and yet the strength of the legs expressed in the prominent hind-quarters, the slender hoofs terminating in a point, the mobile ears extended ó all this is the fruit of most accurate observation embodied in the clearest and simplest form. And in the picture as a whole how the impression of speed, the fleeting, nay, the instantaneous has been seized! Just in this attitude we might espie the timid beast in freedom in his native haunts before he takes to flight at the appearance of his foe, man.

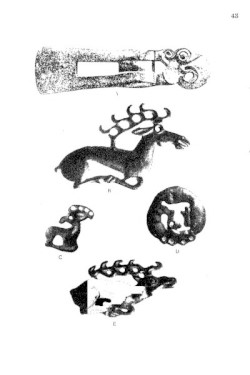

It is a unique contradiction that is here embodied; a conjunction of rigorous stylization with the highest verisimilitude. But this very contradiction is typical of the whole of Scythian art, and not of Scythian art in the narrow sense only, but of the approximately contemporary art of Siberia and even of the Kama region in North-east Russia. We can at once confirm this statement by the remark that in the later Bronze Age of Siberia, which cannot be very far removed in time from the Scythian period, bronze plaques with precisely the same figures are very common. Only here curiously enough the motive often appears in forms already degenerate. Frequently the legs are no longer separated but are depicted as running into one another, so that a sort of long rod seems to lie under the body; however, a transverse dent on this rod betrays the original position of the legs underlying the conventionalization (Plate 43 B). At the same time the correct treatment and the characteristic position of the legs are also found as our illustrations show (Plate 43 E). The reader can see that all the peculiarities of the motive are preserved.

(33/34)

Even the presentation of the antlers with spiral or hooked branches is the same. We find a very similar representation of the antlers on the Siberian bronze mirror in the Hermitage (Plate 41 [Ůž. Ūŗ ŮŗťÚŚ ›ūžŤÚŗśŗ]). Identical bronze plaques representing stags are said to have been found in the Kama district, yet it is uncertain, even if the reports be reliable, whether these were not Siberian imports. In other cases we shall meet plenty of evidence for the identity of this artistic province with the Siberian and the Scythian in the form of unmistakably local products.

It is important to note that, especially in Siberia, the so-called stag figures often allow us to perceive that the animal represented is not a stag but an elk. The conformation of the heavy drooping muzzle leaves no room for doubt on this point. The elk is very plainly depicted on the beautiful wooden plate from the Altai region now in the Hermitage (Plate 59 [√› »Ū‚.Ļ1122/11]). The peculiarities of this animal are characteristically reproduced in the heavy muzzle, the broad palm antlers and the exaggeratedly long limbs.

Besides this motive of the crouching stag or elk with outstretched head we meet manifold variants upon similar representations of the same animals. More rarely other animals, particularly the wild goat, are depicted in the same attitude.

The stag frequently appears in Scythia in a very similar pose, but with the head erect. The limbs are folded beneath the body as before, but the antlers are rather differently treated (Plate 3 B&F). They spread out more widely and the hinder branches are longer and fill up the whole angle between the figureís neck and back. We clearly see the effort to comprehend the whole subject in a compact outline with a view to decorative effect. That striving after a decorative compactness in the motive is also characteristic of Scythian art. On the plaque from Kara-Merket in the Crimea (Plate 3 B), we observe that the two first

(34/35)

and the last antler-branches have been transformed into the heads of birds with hooked beaks in just such a decorative fashion. In the case of the front branches these birdsí heads are turned topsy-turvy; the third is pointing straight down on to the stagís back. The animal is depicted in a similar way with the head upraised rather than stretched out on some of the Siberian bronze plaques (Plate 43 B).

The motive of the same animal in a like pose but with the head turned back over the shoulder is also very common in Scythia. Two variants may be distinguished. In one the head is turned half round so that it comes to lie along the line of the spine and nestles into the back just as the feet are tucked up tightly against the belly. Alternatively the animal has twisted his head round in the plane of his body and rested it sideways against his flank so that the head falls within the outlines of the frame. Both postures are equally natural and can be observed in nature. In the first variant the elk often figures on gold plaques. The head is most clearly portrayed on the plaque purchased at Maikop in the Kuban district (Plate 3 C). The most extreme contortion of the neck is shown on a plaque from Solokha, a grave in the Dniepr region (Plate 3 G); on it, the muzzle is nestling in the hollow of the back. The most conventional treatment is seen on the plaque from a tomb in the Kuban delta (Plate 3 H). In all these cases ó only one example of each type is reproduced on the plate ó the composition remains quite uniform. The antlers, too, are always represented in precisely the same manner curiously shortened. From the forehead rises a bent rod, following the contour of the head and terminating in a birdís head, again inverted, the beak of which reproduces the spirals of the antler-branches.

The wild goat is treated in just the same way in the districts

(35/36)

of the Kuban, Don and Dniepr. His horn is not bent over the head to the back but follows the arch of the neck in quite a natural position (Plate 3 D).

The same motive is also repeated in bronze. The bronze plaque from the Kiev Government (Plate 4 B), the bottom of which ends in a figure, half the paw of a beast of prey and half the talon of a bird, is surmounted by an elk with its heavy muzzle and short but palm-shaped antlers clearly marked. Stylization has advanced further on a plaque from one of the so-called Graves of the Seven Brothers in the Kuban delta (Plate 4 C). Here the elkís muzzle is still distinctly recognizable, although it is very much elongated. The antlers, too, are characteristically broad. But they spread out decoratively in two symmetrical divisions as if viewed full-face, and tower high above the head.

On other plaques from the same grave we meet the second variant of the motive. The stagís head is laid sideways along his flank so as to cover the whole body as far as the hind-quarters (Plate 4 A), the antlers once more spread out decoratively over the head in two symmetrical divisions, in one plane.

In all these examples, parallels to which might be quoted from Siberia (Plate 44 C), we meet the same characteristics: the motive is curiously and regularly stylized; at the same time the representations are always thoroughly alive and true to nature; the appreciation of the forms of the animal world is deep and highly developed.

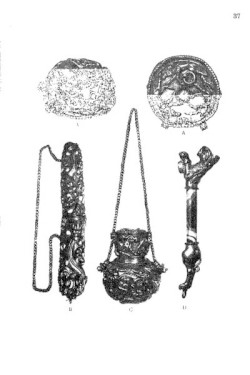

Let us next examine the representation of a standing stag with his head turned back on a gold plaque in the collection of the Moscow Historical Museum (Plate 3 A). How natural is the headís pose! how truly is the grace of body, muzzle and ear reproduced! And yet a hornless elkís head is attached, purely ornamentally, to the shoulder! The most characteristic

(36/37)

feature is, however, the position of the legs. How well all the lightness and agility of the beast is thereby expressed. If we look closer, we note that the hoofs are not really depicted as standing on the ground but with the toes turned down. We get the impression that the legs are hanging down loose. This is no accident; there are other examples, too, even from Scythia, and it recurs in more marked form in Siberia on the bronze mirror in the Hermitage collection (Plate 41). All the stags or elks and the goat there depicted are floating with hanging legs as if suspended in mid air. Note, too, that the ground is not indicated; the figures are completely cut away from all environment. The artist has reproduced with the most lifelike accuracy and the strongest emphasis on characteristic traits the impression gained from immediate observation of the animals. Abstracted from all context, without any association with ideal constructions, alone and isolated, the fresh living impression, the memory-picture, has served as the artistís model. We might be tempted to speak of a primitive impressionism, but that we are dealing at the same time with such a markedly decorative stylization.

In addition to figures of complete animal forms, motives based upon individual parts of the body, especially the head, were much in vogue. Deerís and elkís heads are also used as independent motives. The impulse to decorative stylization is still more marked in such partial representations.

We have already met the elkís head in profile as an independent ornament upon a figure of a stag. It appears also quite by itself. It is always very much stylized. The pendancy of the muzzle is emphasized in an exaggerated way. Occasionally the outlines of the muzzle in front nearly form a right angle, as happens particularly in objects from the Dniepr district, both of bronze

(37/38)

and of carved bone (Plates 5 A&C and 32 E). The contours are more rounded on plaques from the Crimea and the Kuban delta (Plate 5 B). But, en revanche, the jowl droops antlers are extraordinarily stylized. Two branches in the shape of birdsí heads sprout out on either side of the forehead over the eyes. The birdsí heads are once more inverted so that their beaks may form the proper volutes. Between them grows a palmette, while on Fig. A another grows between the ear and the nape of the neck. This is a clear instance of the penetration of Scythian culture by Greek elements. Typically local on the other hand are the volute-shaped mouldings, often encircling the mouth and nostrils (Plates 5 B&C). They recur in a very similar way in Siberia on a double figure of elksí heads in carved bone (Plate 60 C). Such reduplication of the motive is also met in Scythia. A fine example is the bronze plaque from the Dniepr district (Plate 5 D), which, like the Siberian specimen in bone, served as a clasp. Two elksí heads in strict profile, with but one eye and one ear each, are here opposed with the muzzles and necks touching. A strip of bronze purely utilitarian in purpose unites the ears above the heads. On the bronze specimen from Siberia as on some representations of single elkís heads the eye, too, is made unnaturally big and stands out as a round boss with a flanged edge right on the outline of the head. The stylization of the ear is also characteristic; in almost all cases the hair on the inside is suggested by parallel lines (Plates 5 A, C & D). In one of these elksí heads the thick mane of the neck provides an effective border for the outline behind.

We see that the elk constituted a clearly marked, independent and fairly widely diffused motive even in Scythia. To show that the same motive was current in the third artistic province

(38/39)

ó North-east Russia ó we may refer to the exquisite carving in bone which was found in that region and is certainly a local product (Plate 64 F).

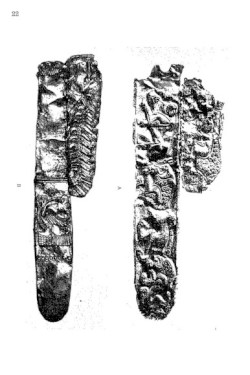

Beside the elkís head the motive of the stagís head lived its own independent life. It is characteristic of it that the antlers are fruitfully used for decorative ends. In the simpler figures the antlers generally tower over the head. They are represented thus on a series of bronze stagsí heads from various graves in the two adjacent groups of barrows known as the Great and Small Seven Brothers in the Kuban district (Plate 6 B, C & D). Here, too, some branches are frequently not naturalistic, but shaped decoratively into the form of birdsí heads (Plate 6 A). In such decorative stylization the antlers of the stagís head on the side plate of a gold sword-sheath from a grave at the mouth of the Don are represented in an exaggerated and already rather degenerate fashion (Plate 22 B). Here extended birdsí heads in an endless row perch as branches on the antler, which ultimately terminates in a half Greek, half Oriental palmette. This motive of the stagís antlers with birdsí heads also appears quite by itself and in fact without any indication of the head on late and degenerate products. How fruitfully the motive of the stagís antlers was used for decorative purposes is shown by the illustrations on Plate 7, all bronzes from the Kuban district. In the middle of the girdle-plate the forequarter of a stag ó head, foreleg, and antlers ó is represented (Plate 7 A). The antlers are spread out in some incomprehensible way into two symmetrical halves, each branch being a very long drawn out birdís head. To left and right lie stagsí heads. That on the left is preserved whole; on the right, the head itself has been broken off and only the antlers, formed as on the other side, have survived. The antlers are again divided

(39/40)

each pair into two symmetrical halves, each one consisting of three birdsí heads, of which the middle one projects furthest. The birds on either antler are facing in opposite directions. The several corresponding birdsí heads vary considerably in size. In a like manner, nearly the whole of the object on the plate decorating the bridle-piece is framed by the antlers of two stags, heraldically opposed, with the heads turned backwards (Plate 7 C).

In these specimens, however freely the antlers are used for decorative ends, they are still understood more or less for what they are. But in the next two examples they are wholly dissolved into a purely ornamental scheme. On the plate adorning another bit from the same find in the Kuban district (Plate 7 B), the stagís head is still quite clear, with its extended ear, its eye and its firm set muzzle. The antlers have, however, become a mere ornament, and in the midst of their decoratively interlacing lines appears a sort of inverted Greek palmette. On the poletop from the Kuban district the meaning of the motive has already been entirely forgotten. Of the stagís head, only a thoroughly degenerate ear and the tip of the muzzle survive, the eye has disappeared and the antlers have grown into a senseless medley of volutes (Plate 7 D). These are good examples for showing how in this art province the organic animal form is the original element; the purely ornamental or vegetable shapes are secondary and generally first arise out of the degeneration of animal forms.

In the whole domain of the Scytho-Siberian animal style the birdís head motive is perhaps even more widespread than the stagís or elkís head. We have already encountered it several times ornamenting antlers. But it is also very common as an independent motive. It is most definitely elaborated on the

(40/41)

magnificent bronze plaque from one of the Seven Brothers (Plate 8 A). The palmette at the back is again naturally to be ascribed to Greek influence. On the other examples on this plate too the characteristic features of this motive are well marked, Perhaps the purest is the specifically Scythian stylization on the beautiful bronze bridle-piece from the Kuban district (Plate 8 D). The hooked beak rolled into a regular scroll is exaggeratedly big. In front of the eye the cere at the base of the nose is clearly marked and has been deliberately emphasized for decorative effect. The cere and the hooked beak are characteristic marks of birds of prey and at the same time typical features of the Scytho-Siberian stylization. Thus on this motive too we recognize the same quality: the artist selects the characteristic features of the animal form as he has observed them in nature, restricting himself most rigidly to the absolutely essential elements, uses these as the basis of a representation, and then works it up as an independent element in decorative fashion.

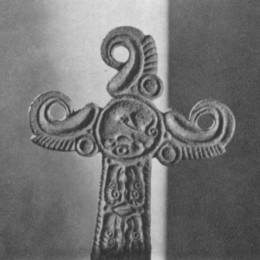

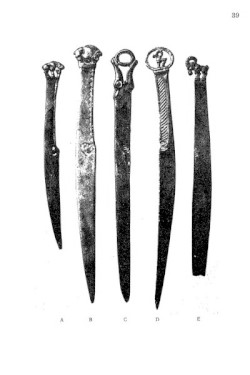

The reader will notice how repeatedly this emphasis on the cere recurs everywhere, both in Scythia and in Siberia and the Kama district. The birdsí heads on the dagger-hilts from Siberia (Plate 40), the similar birdís head on a bronze from the Kama district (Plate 64 E), and all the specimens from Scythia reproduced here exhibit the same peculiarity in different variants. This feature is especially marked on the cruciform bronze girdle-plate found in the necropolis of Olbia (Plate 9). It reappears again on the bone comb from Poltava Government, here indeed repeated twice on the same head (Plate 33 A). The birdís head motive is also common in gold work; examples are collected on Plate 11. Four birdsí heads are perched in a row on a vase handle from the Solokha grave (Plate 11 H). In the case of another vase handle, also of typically Scythian

(41/42)

form, the whole object is wrought into the form of a birdís head (Plate 11 G). At the back of the head perches another smaller birdís head, the scroll of whose beak passed over into the eye of the larger bird, making the whole a regular puzzlepicture. The motive is also wrought in iron, most commonly on sword-hilts (Plate 10 A), but also on bridle-pieces (Plate 10 B). The head on the iron knife from Kiev Government illustrated on the same plate is peculiar (Plate 11 C). The outlines are those of an elkís head, but the long slit for the mouth and the cere below the eyes are traits belonging to the birdís head. It is a combination of two originally distinct motives.

We possess two masterpieces of Scythian decorative art devoted to the birdís head motive. Both are equally perfect, although the one is a veritable miniature while the other is on a monumental scale. The first of these is a piece of bone carving found near Kerch. The whole object, here reproduced in its natural size, represents plastically a birdís head (Plate 32 A). At the back a little beast like a hare with the legs curiously tucked up has been carved. This animalís tail is long drawn out, passes along under the rear edge of the birdís head, then turns up and forms the beakís cere in the guise of the forequarters of a second hare. In the place of the nostril holes on the beak yet another little animalís head has been carved, and its long ear in the form of a double ridge follows the contour of the beak. The ingenuity displayed in the invention and execution of such a complicated little scene fills us with amazement.

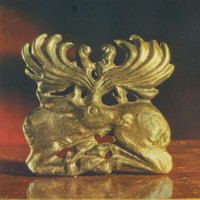

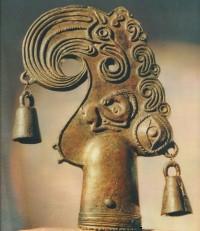

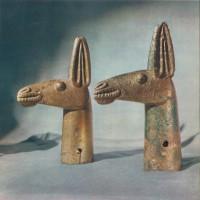

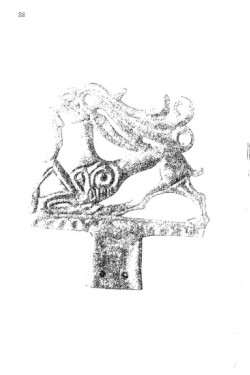

The second masterpiece is a pair of bronze pole-tops in the form of birdsí heads from Ulski Aul in the Kuban district (Plates 24 and 25 [Ůž. Ūŗ ŮŗťÚŚ ›ūžŤÚŗśŗ: »Ū‚. ĻĻ ů.1909-1/111 Ť ů.1909-1/112]). The one is almost smooth, the surface of the other is richly decorated. The pure contours of the head are admirable, the great pointed scroll of the beak contrasting with

(42/43)

the sharp edge of the long prominent cere below the base of which the great eye stands out in relief right in the corner of the figure. Along the projecting fold of the cere, smaller birdsí heads have been represented by parallel lines in relief. On the more elaborately decorated specimen the scroll of the beak has also been adorned with such parallel lines in relief. In the middle of this figure yet another birdís head has been depicted facing the opposite way. Below it, the figure of a wild goat in the already familiar attitude, with head turned back and legs tucked up, has been moulded in relief. Little bells were once suspended from the now partly broken loops at the edge. These two pole-tops are among the finest achievements of Scythian art in the decorative treatment of organic bodily forms.

A feline beast of prey plays a prominent role in Scythian art. The representation of this animal must be attributed to southern influence since neither the panther nor the lion is native to southern Russia. It is, however, characteristic that occasionally even in Scythia, but more especially in north-east Russia and Siberia, other animals, among which the bear, an animal as much at home in those wooded regions as the elk, distinctly recognizable appear as the basis of the very same motives which in Scythia are based upon our feline beast. There are three chief motives derived from this beast.

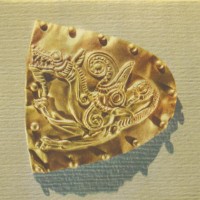

The first is as beautifully and brilliantly represented by the shield blazon enriched with coloured inlays of glass paste and amber as is the stag on a similar emblem from Kostromskaya Stanitsa. It is a gem from the rich treasure of Kelermeskaya Stanitsa, likewise in the Kuban district (Plate 12). The cat-like beastís legs slant forward and his head hangs down in front of his paws.

This motive is common on gold plaques (Plate 11 D). Both

(43/44)

borders of the gorytus-plate depicting stags are occupied byrepetitions of this motive (Plate 2), and a column of similar beasts adorns the gold plate covering a sword-sheath (Plate 23 A). The gold plaques from Kharkov Government in the Moscow Historical Museum are very similar (Plate 11 A). But here the position of the legs is rather different: the feet are drawn up closer to the body; the paws and the bush of the tail have grown into birdsí heads; a small birdís head perches on the beastís lower jaw and a larger one decorates his shoulder.

The beasts often adorning the handles of the graceful Siberian knives sometimes assume a very similar attitude. These animals are generally depicted as boars, but bears, too, can often be distinctly recognized, and this motive was probably the original one (Plate 39 A & B). The little bear engraved on the elkís head from North-east Russia evidently belongs to this family (Plate 64 F). The characteristic pose of the head is precisely the same and is just as proper to a bear as is the outstretched position to elks and stags. So we may reasonably assume that the whole motive had been originally inspired by a bear.

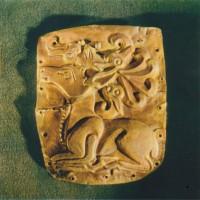

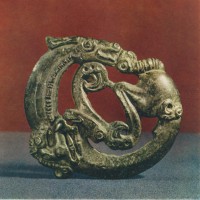

On each paw of the great beast from Kelermeskaya a little doubled-up beast is depicted. The same figure is repeated six times on the surface of the great beastís tail (Plate 12). It is the second motive to be discussed. Here it is not as clear and comprehensible as elsewhere. It comes out most simply and distinctly on the exquisite gold plaque from Siberia in the Hermitage collection (Plate 45). The beast is curled up into a complete circle. The head hangs down from the long arched neck and almost reaches the tail. The shoulder is powerful and stands out like a great boss. From it the foreleg is extended in an arc concentric with the curve of the neck. The whole body, too, is drawn out and bent into a semicircle. The hind-quarter

(44/45)

stands out as strongly as the shoulder and thence the hind leg is extended towards the inner curve of the belly. The tail is bent round into the middle of the figure between the rump and the nose; often, however, it occupies only a little space between the rump and the jowl. It is an unique motive and very conventionally treated. But incomprehensible though it be at first sight, it was none the less very popular. In smaller, often rather degenerate, representations it is common in Siberia and the Kama district as well as in Scythia (Plates 14 C&D, 43 D and 64 D). It is to be remarked that it also appears oh carved bone (Plate 32 B&C), when the rendering of the eyes, nostrils and paws as circles closely resembles what we saw on the gold plaque from Siberia. Perhaps the most beautiful example of this motive is the great bronze plaque from a grave near Simferopol in the Crimea (Plate 13 [√› »Ū‚.Ļ ū.1895-10/2.]). Only the beastís head is here rather different. It has an elongated, relatively pointed nose as is often the case with this theme (cf. Plate 14 D). The paws take the form of birdsí heads and the figure of the wild goat with reverted head is again depicted in relief on the shoulder. Below it a very stylized elkís head has been added to the fore-paw. The horn of the wild goat and the feline beastís tail also terminate in birdsí heads.

This motive is again very well represented by the bronze button from one of the Seven Brothers (Plate 14 B). Here it is obviously a lion that is intended. The mane is conventionally rendered by long parallel strokes on the neck; the shoulder is free of hair. But then the rest of the body to the hind-quarters is again decorated with radial strokes. We are in doubt whether they are meant to indicate mane or ribs. In any case the Way that the shoulder and the hind-quarters stand out is typical.

With slight modification in the position of the legs the

(45/46)

same motive recurs in the circle in the middle of the cruciform plaque from Olbia (Plate 9). It reappears, quite regular in composition if a little degenerate, in the Ananyino culture of North-east Russia (Plate 64 D), and in other probably contemporary remains.

The peculiarities of the third motive are as follows: the body of the beast which is represented sometimes reclining, sometimes standing, is depicted in relief side face. The beastís neck and head are plastically turned forward to face the spectator. The finest specimen of this motive is a panther figure of solid bronze overlaid with gold-foil from the so-called Golden Barrow near Simferopol in the Crimea (Plate 15 A). The beastís body had been adorned with coloured inlays but leaving the shoulders and hind-quarters plain; but only the leaf-shaped cells that received the inlays remain. Two bronze figures from the Dniepr district also exemplify this motive (Plates 15 , B&C), In both specimens the tail is depicted in the guise of a birdís head. It is to be noted that in a grave near Voronezh on the upper Don a silver reproduction of the same motive was found which obviously represented a bear. From the Altai in Siberia comes the carved wooden figure of an ungulate animal which is represented in precisely the same attitude (Plate 63 B). Thus in these three motives we can once more observe the identity of artistic style in Scythia, north-east Russia and Siberia.

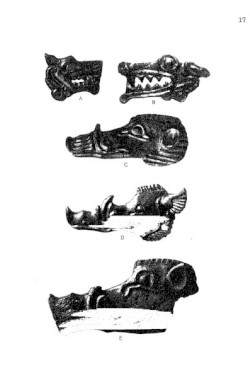

That can be as definitely proved with the aid of the motive derived from the head of a beast of prey. The independent representation of a lionís or pantherís head occurs relatively often in Scythia. The gaping maw discloses the powerful incisor fangs. The whiskers on the upper lip are seldom overlooked. In Scythia the motive is found both in bronze (Plate 16), and on a sadly damaged piece of carved bone in the Moscow

(46/47)

Historical Museum. On the other hand, we possess an exquisite specimen from Siberia. It is a wooden plaque from the Altai in the Hermitage (Plate 60 G). The stylistic treatment is admirable with scroll lines round the ear and lower jaw. Cunning is livelily expressed in the oblique eye, and the structure of the maw of a ravening beast with the two great incisor fangs in front and the smaller molars arrayed behind them is happily reproduced. The stylized rendering of the whiskers on the upper lip is also very marked here; they are indicated by parallel curved incisions. Although we have no such marked instance of this feature on purely Scythian objects from south Russia, we must ascribe this whisker-motive to western influence since it is typical of the representation of the lionís jowl in ancient Anatolian art whence it was taken over by archaic Greek art.

The lionís or pantherís head viewed full face is another comparatively common motive. In Scythia, in addition to small, much stylized representations like that on the gold plaque here illustrated (Plate 11 B), larger examples are also available. The whiskers are, however, very strongly marked on the gold plaque. This motive reappears in much the same form in Siberia (Plate 60 F), and also in the Kama district (Plate 64 C). Then we meet it again on a larger scale but still transformed by extreme stylization in horn and wood-carvings from the Altai (Plate 60 D and 62 [√»Ő ĻőÔ.Ń 1803/64]). We shall have occasion to return to these representations later on.

Besides the panthersí or lionsí heads we also meet isolated representations of that sharp-nosed head which we saw on some of the animals curled up into a circle. Two examples are shown here from Scythia where this motive is relatively rare (Plate 17 A&B). Characteristic is the long pointed jowl with open maw. Behind the eye stands an ear; it is generally small but on the

(47/48)

second of the heads already manifests a tendency towards decorative extension. The weird effect of the other head is enhanced by the representation of a bird's head on the cheek-bone. In fact, it is hard to say what animal is actually intended; we are evidently confronted with a very highly stylized motive. However, on the exquisite bone spoon from a grave in Orenburg Government, it is unmistakably a bear that is depicted with such a head (Plate 31 A). The outlines of the great unwieldy body with its broad, powerful limbs, are engraved on the back of the spoon with admirable certainty. Framed within the contours of the bearís body another elongated beast is curled up with a similar pointed head and a long ear. The bearís head projects far forward and is carved to form the handle of the spoon. Unfortunately the upper edge of the head has been broken off so that the snout looks more pointed than it originally was. We must complete the picture with a distinct, probably scrollshaped, representation of the nostrils as other examples of the same head show. Nevertheless, it is clear that we are dealing with the same motive which here is evidently intended to represent a bearís head. The conformation of the beastís jaws with two long incisor fangs in front and half-rounded teeth behind them is here typical.

This trait is preserved in another bone carving from Orenburg Government (Plate 31 B), and in the bronze examples from Scythia (Plate 17 A&B), which have already been further transformed by stylization. For comparison, let us look again at the little figure of a bear engraved on the elkís head from North-east Russia (Plate 64 F). The outline of the whole beast is here much more cursorily sketched; still the bearís head exhibits an unmistakable similarity to the motive just discussed. The ďbearsĒ again on the bronze Siberian knives (Plate 39

(48/49)

A&B) have very similar heads. So we may well assume, despite the astonishment provoked by such a hypothesis, that this peculiar motive is based upon a representation of the bear. Of course, this motive is very far from its original condition and exhibits a constant tendency to contamination with other motives or to purely ornamental stylization. In Siberia it very often happens that the snout is drawn out to a sharp point and comes to resemble a wolfís head, as for instance in the case of the double figure on a bronze mirror-handle (Plate 44 A).

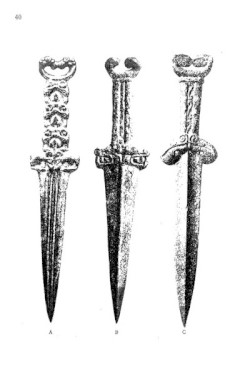

Occasionally whiskers are seen on the upper lip and recall the pantherís or lionís head. We find this in Scythia on one of the bronze heads (Plate 17 A), and also in a wood-carving from the Altai (Plate 60 A). On the latter the volute into which the nostril has been transformed is very typical; on the second bronze head from Scythia the nostril is represented in a similar way (Plate 17 B). On the two heads adorning the guard of a Siberian dagger (in the Hermitage), with iron hilt and bronze blade ó an unusual combination ó the nostrils are in each case represented as scrolls (Plate 40 B). And we meet the motive characterized by precisely the same peculiarity in North-east Russia. Particularly satisfying is the representation on the bronze axe (Plate 64 A). But just the same traits are exhibited on a little bronze plaque (Plate 64 B), depicting this head twice, but this time the lower jaw is omitted in each case so that we get two heads with two eyes and two nostrils, but only one mouth.

We have dwelt at some length on this motive because in itself it is rather incomprehensible and at the same time because it is of importance in connection with the influence exerted by the Scytho-Siberian repertoire upon other cultures, as we shall later see. In Scythia it played a comparatively small part and was soon misunderstood. That is natural since the bear, a forest

(49/50)

animal, is not met on the steppe, so that the artist lost immediate contact with his model. It is not, therefore, surprising that in Scythia boarsí heads appear as well in outlines that recall this motive (Plate 17 C, D, E). In Siberia, too, as we have already seen, the bearís figure when no longer properly understood turned into a boar. However, the boar was an animal known also to Greek artists, and it is possible that they have contributed to the transformation of the motive.

To complete our survey of the motives of the Scythian animal style several examples of two further motives are grouped together on the next plates (Plates 18 and 19). They were fruitfully employed on horse-trappings for the decoration of frontlets and cheek-pieces. They appear also on other objects, but not so often. These motives are derived from animalsí feet. The representations of a hoof with the adjacent fetlock joint are admirable and in perfect harmony with the best qualities of the animal style. The feeling for the organic structure of the animal body fills us with admiration. The figure is clearest on the bridle-piece, terminating in two opposing hoofs (Plate 18 C). On the joint, the delicacy and mobility of which are admirably rendered, the short fetlock is indicated. Below comes the pastern and right at the end is set the hoof, sharply outlined and gracefully shaped. These three parts are always carefully distinguished, however stylized the figure may be. Consider now the small dagger-like object surmounted by a pantherís head (Plate 18 A). On the back it is provided with a strap-hole so that it must have been a horse ornament, very likely a frontlet. Here the hoof is very long drawn out and ends in a regular point. The third example, likewise a horseís frontlet, is yet more stylized (Plate 18 B). The representation on the upper part of the object is obscure; only the little Greek palmette is plain. The lower

(50/51)

part once more forms a hoof. The fetlock joint is here distorted, but its elongated form is only an exaggeration of what is given in nature. The fetlock is duplicated and hangs down right to the hoof.

An instructive evolutionary series is provided by the motive of the separated hind legs of a leonine beast of prey. We meet it quite clearly marked both in the representation of the complete hind-quarters with both legs (Plate 19 A&C), and that of one leg alone. In addition, highly stylized examples occur such as that illustrated on the top of the plate to the right (Plate 19 B). The feet are no longer the paws of a savage beast but plainly the birdís talons. The rear claw is turned the opposite way to the rest, which is natural on birdsí legs but is impossible in the case of paws. We have already observed such hybridization between two motives, and this particular case we might illustrate by the example depicted beneath a reclining elk (Plate 4 B). Here, too, belongs the figure under one of the feline beasts facing the spectator (Plate 15 C); this time it is obviously a birdís claw. The last example (Plate 19 D) shows how this motive, like that of the stagsí antlers, can be resolved into a mere ornament.

The repertoire of Scythian art is not, of course, exhausted with the examples that we have cited. But they will have been sufficient to serve as an introduction to the comprehension of this remarkable style. The exceptional faculty for naturalistic reproduction of animal forms has been amply illustrated and at the same time all the figures bear witness to a great talent for decorative stylization. These two tendencies are mutually interwoven, and, however contradictory their nature may seem, are combined to an organic unity in this style which endows all its creations with a high artistic merit. Of course, a certain amount of habituation is needed for an insight into the strangely stylized

(51/52)

figures. Nevertheless, the more they are studied, the more impressive they appear. The whole fancifulness of this style is at bottom only apparent. All the curious combinations of various animal forms in a single figure are far from being so fantastic as they seem at first sight. Generally we only find that individual parts of animals, above all parts important for the organic structure of the frame, have been ornamented with figures of other animal forms. In this way joints or shoulderblades are especially often emphasized, or the individual branches of the antlers marked off from the rest. In representations of heads it is often the cheek-bone that is thus adorned. This procedure is therefore only a way of emphasizing such parts of the body as are constructively significant for the total presentation.

Such fantastic hybrids as the two monsters on Plate 20 are rare. Below we see a lion with stagís antlers, the branches of which are represented by birdsí heads (Plate 20 B). The gold plaque illustrated above it (Plate 20 A) presents a figure composed of several heterogeneous elements and betrays obviously foreign influence to an unusual degree. The monsterís back ends in a purely Greek swanís or gooseís head, which shows us that we have to deal most likely with the work of a Greek craftsman imitating Scythian style. The paws of the monster belong to a lion, its head strongly recalls the motive of the Scythian ďbearsí heads,Ē but stands half-way between that of a Greek sea-horse and a Chinese dragon; its wing, again, has the form of a Scythian birdís head, with very prominent cere and a pointed ear. We must also ascribe to foreign influence, this time Assyrian or Anatolian, though perhaps transmitted through Greece, the scorpion-like cartilaginous tail of the lion on the plate decorating a scabbard (Plate 22 A). The fabulous beast on another scabbard from the Don delta (Plate 22 B), is half

(52/53)

made up of the specifically Greek winged griffin with lionís paws and birdís beak. It is not quite clear whence came the other elements of the figure ó the extraordinarily wide fishís tail and the snake whose head the griffin is biting; they are not Scythian, at least, in such a composition.

As we have said, such really fantastic figures are the exception in Scythian art. The latter gives the impression of being fantastic rather because we are dealing not with a realistic and naturalistic style, the repertoire of which is inspired by logical rigorous observation, but with a style that is best described as impressionistic.

The peculiar direction taken by this style is perhaps most clearly revealed in the striking circumstance that the Scytho-Siberian animal style exhibits an inexplicable but far-reaching affinity with the Minoan-Mycenæan. Nearly all its motives recur in Minoan-Mycenæan art. The French savant, Salomon Reinach, was the first to call attention to this resemblance in his interesting article on the representation of the gallop in the art of ancient and modern peoples. He shows that the figure of the so-called ďflying gallop,Ē in which the animal is represented stretched out with its forelegs extended in a line with the body and its hind legs thrown back correspondingly, is at once characteristic of Minoan-Mycenæan art and foreign to that of all other ancient and modern peoples; it only recurs in Scythia, Siberia and the Far East. He further points out that this motive is not true to life but nevertheless reproduces in a most effective manner the impression of swift movement. Now to reproduce the immediate sense impression, not accurately but in a lively and lifelike way, was the very aim of Scythian art. Unfortunately it has not been possible to illustrate this motive here. But the same feature is clearly marked in another motive. Let us

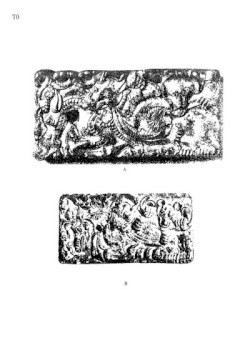

(53/54)

examine the Siberian gold and bronze plaques depicting scenes of fighting animals (e.g. Plates 46, 47 and 55 C). How often are the animals depicted with the body so twisted that the forequarters are turned downwards, while the hind-quarters are turned upwards! Can the agonized writhings of a wounded beast or the fury of his assailant be more simply rendered? And yet the motive is as conventional as one could wish. Indeed, it is often used apart from all context in individual figures. An instance is seen in the bronze bit from one grave in the Seven Brothers which has been fashioned in the form of a lion twisted in this way (Plate 14 A).

Other motives of the animal style, too, reappear in Minoan and Mycenæan art. We may cite the animals with hanging legs and those which are curled almost into a circle. Conversely the standard motive of the Minoan-Mycenæan lion, often represented in the Aegean with reverted head, reappears again in Scythian and Siberian art.

How are we to explain this far-reaching kinship in aim between the two artistic schools? It remains on the face of it a riddle. Immediate relations between Minoan-Mycenæan and Scytho-Siberian civilizations are unthinkable; the two are too widely separated in space and time. An interval of some five hundred years separates them. Nor has the least trace of Mycenæan influence on South Russia, either during that civilizationís life or later, yet been discovered. Still, the kinship between the two provinces of art remains striking and typical of both of them. Here as there art unites in itself the highest realism and naturalism of expression with the most rigid decorative stylization.

The exceptional decorative talent of Scythian art is conspicuously illustrated in the great ingenuity which the artist displayed

(54/55)

in filling up a shape determined by practical ends with animal figures so as to leave a minimum of empty space. For this purpose a series of small figures is sometimes grouped together or alternatively the whole object is fashioned in the shape of an animal. So, for instance, the frontlets of bridle-trappings are occasionally shaped like fishes. We have two fine specimens in gold-leaf from the Barrow of Solokha (Plate 21); from Siberia comes an analogous frontlet with only this difference, that one instead of two fishes composes its outline. The two wing-like pieces belonging to the same bridle are shown by the parallel flutings to represent earsó compare the stagsí and elksí heads.

In the same way handles are often fashioned as figures of animals, as for instance the handles of a gold vase from Siberia (Plate 58), or the handles of the huge Scythian bronze cauldrons. On the specimen from Kelermes (Plate 29), here illustrated, where only one of the two handles has survived, it is a joy to see how well the stylized horn of the wild goat is adapted to the practical function of the ornament. In fact, this figure is a standard type as the handles of the bronze mirror and a bellshaped object from Siberia show (Plate 44 B&C). In like fashion the round nob-handles affixed to rods in the middle of the circular bronze mirrors are often decorated with animal forms. On the mirror from the Samokvasov collection in Moscow (Plate 30 2), it is once more the reclining wild goat with reverted head and tucked up legs that forms the handle.

The gold plates from sword-sheaths here illustrated are excellent examples of this skill in filling up a given object with animal figures. How perfectly the contours of the two wild goats on the upper part of the scabbard from Poltava Government (Plate 23 A) fit the form of the enlargement that receives the swordís guards! How completely the device at the side of the

(55/56)

sheath proper that serves to attach it to the sword-belt is covered over by the stagís head and its antlers on the gold plate from the Don delta (Plate 22 B). How admirably the twisted hindquarters of a lion have been adapted to the lower edge of the plate covering a sheath from the Don district (Plate 23 A). The lionís figure has been no less skillfully adjusted to the shape of the two projections at the side of the scabbard-plate from Solokha (Plate 23 B). Similar lions grasping deersí heads in their forepaws occupy the two upper fields on the sheath; below them come two motives inspired by Greek influence ó the griffin with reverted head and notched mane but no wings, and the panther whose head is turned round to face the spectator quite in the typical manner of archaic Greek art. Finally, the round chape is entirely taken up by a lionís head, viewed full face, which is frankly degenerate. The upper half of the circle is occupied by the ears with characteristic parallel flutings and the fretted mane between them, the lower half beneath the eyes by the upper lip with the whiskers in the same stylized rendering as the ear-hair.